Showing posts with label race. Show all posts

Showing posts with label race. Show all posts

Wednesday, July 20, 2022

Horse by Geraldine Brooks

Hardcover, 416 pages Pub June 2022 by Viking, ISBN13: 9780399562969

Horse, the story of a great racing stallion from Kentucky named Lexington, encompasses an arc of American history that cuts still today. Australian author Geraldine Brooks puts her finger on the sensitive places in America’s living history which we as a society have not yet resolved: our relationship with America’s early racial legacy, slavery.

The colonial powers of the 18th- and 19th centuries all have complicated histories with race, but America stands apart as a country built explicitly on the notion of equality for all men. The founders just didn’t ‘cotton’ the connection properly between Blackness, economic prosperity, rights and freedom. The Civil War was meant to set them straight, but it didn’t actually do that. There was nothing civil about it…then or now.

The horse Lexington, described on two continents as the “greatest racing stallion in American turf history,” and slavery have a shared history, both in reality and in this fiction. There are pre-Civil War written and painted records of Lexington’s groom and trainer, both Black men in Kentucky, a state which would hover in-between the Union and Confederate armies and be bled by both.

We hear the story of a White Union soldier who initially finds himself seeking out prisoners “to better understand their minds.” Gradually, he realizes those men “were lost to a narrative untethered to anything he recognized as true.” Author Brooks connects our history with America today.

In a Brooks novel, readers enjoy the author’s passions…for history, science, horses, art…and for her native land, Australia. Brooks doesn’t give her own country a pass in the race relations area, giving voice to a critic of Canberra’s policies. She successfully details examples of microaggressions, some that go out into the world and are recognized for such, just as they land, by all witnesses.

The embarrassment of recognizing one’s own prejudices spills onto the reader, making us cautious but willing to learn more about how these impulses buried deep inside suddenly materialize and how they impact those around us. One of the more interesting characters who brings out the reader’s prejudices remains sketched only lightly in the background: a gruff woman of diminished means who throws out on the sidewalk an old and dirty painting of a horse and to whom we impute a nasty attitude totally dissimilar to our own good intentions.

Horse is a wonderful read, filled with surprising discoveries and twists we do not see coming. In the Afterword, Brooks reminds us that her husband, Tony Horwitz, was a Civil War historian who approved of her turn towards this history in her novel before his untimely and sudden death in 2019. What a wonder that this terrific book was birthed in midst of such great sorrow and loss.

Tweet

Tuesday, July 27, 2021

Rhode Island Red by Charlotte Carter

Paperback, 192 pages

Published July 27th 2021 by

Vintage Crime/Black Lizard (first published 1997)

Original Title: Rhode Island Red,

ISBN13: 9780593314104,

Series: Nanette Hayes Mysteries #1

Charlotte Carter. We are lucky to be alive in this time when publishers are doing the right thing for themselves AND for us by republishing terrific, under-read authors. Charlotte Carter is new to me but she is one of the best writers for a kind of hard-boiled mystery reminiscent of Raymond Chandler and the kind of glamour and won’t-look-away savvy of Nina Simone and James Baldwin.

Nanette Hayes is the series. Described as “a Grace Jones lookalike in terms of coloring and body type (she has the better waist, I win for tits)”, Nan is, when we meet her, busking on NYC streets with a saxophone, supplementing part-time work as a translator, French to English.

As far as I can tell, the series is only three novels long, but Carter has such a delicious and particular voice, you’re going to want to read all of this in a rush of indulgence. The first book in the series, Rhode Island Red, comes out July 27, just in time for long hot days in the hammock. August and September bring the last two, Coq Au Vin and Drumsticks. It’s like eating bonbons—very hard to resist.

First published in 1997, Rhode Island Red is written from a Black woman’s perspective and set in New York City just after stop-and-frisk was added to our lexicon. Cops were hated then, maybe even more than now? Even the title is a mystery; we don’t even know what the title means until close to the end but if you were to guess…

Nanette longs for France but grew up in the States as a child prodigy in maths, languages and spelling, of all things. One day another sax street player—a White man a little older than she—shows up needing a place to stay…and who ends up dead within hours.

It’s a complicated story, as it always must be when a stranger gets killed inside one’s own apartment. Nan calls the cops, only to have them question her motivation in bringing him home to her apartment. It’s a good question, one that Nanette will spend the rest of the story asking herself.

Carter wasn’t ahead of her time. She was playing old tunes in the 90s, but they were the anthem of the century. In a sense, she was closing the joint. We as a country are just catching up with her now. Radical. Real. Rhode Island Red.

Tweet

Published July 27th 2021 by

Vintage Crime/Black Lizard (first published 1997)

Original Title: Rhode Island Red,

ISBN13: 9780593314104,

Series: Nanette Hayes Mysteries #1

Charlotte Carter. We are lucky to be alive in this time when publishers are doing the right thing for themselves AND for us by republishing terrific, under-read authors. Charlotte Carter is new to me but she is one of the best writers for a kind of hard-boiled mystery reminiscent of Raymond Chandler and the kind of glamour and won’t-look-away savvy of Nina Simone and James Baldwin.

Nanette Hayes is the series. Described as “a Grace Jones lookalike in terms of coloring and body type (she has the better waist, I win for tits)”, Nan is, when we meet her, busking on NYC streets with a saxophone, supplementing part-time work as a translator, French to English.

As far as I can tell, the series is only three novels long, but Carter has such a delicious and particular voice, you’re going to want to read all of this in a rush of indulgence. The first book in the series, Rhode Island Red, comes out July 27, just in time for long hot days in the hammock. August and September bring the last two, Coq Au Vin and Drumsticks. It’s like eating bonbons—very hard to resist.

First published in 1997, Rhode Island Red is written from a Black woman’s perspective and set in New York City just after stop-and-frisk was added to our lexicon. Cops were hated then, maybe even more than now? Even the title is a mystery; we don’t even know what the title means until close to the end but if you were to guess…

Nanette longs for France but grew up in the States as a child prodigy in maths, languages and spelling, of all things. One day another sax street player—a White man a little older than she—shows up needing a place to stay…and who ends up dead within hours.

It’s a complicated story, as it always must be when a stranger gets killed inside one’s own apartment. Nan calls the cops, only to have them question her motivation in bringing him home to her apartment. It’s a good question, one that Nanette will spend the rest of the story asking herself.

Carter wasn’t ahead of her time. She was playing old tunes in the 90s, but they were the anthem of the century. In a sense, she was closing the joint. We as a country are just catching up with her now. Radical. Real. Rhode Island Red.

Tweet

Wednesday, June 12, 2019

Lead from the Outside by Stacey Abrams

Paperback, 256 pgs, Pub March 26th 2019 by Picador (first published April 24th 2018), ISBN13: 9781250214805

Stacey Abrams learned to not always kick directly at her goal. Watching her stand back and assess a situation can be a fearsome thing. You know she is going to do something oh-so-effective and she is going to use her team to get there, those who mentored her and those she mentored herself. I just love that teamwork.

This memoir is unlike any other presidential-hopeful memoir out there. Abrams has not declared herself for the 2020 race, but running for president is on her to-do list. I read the library edition of her book quickly and wondered why she’d write it this way; she’s a writer and this is written in a workbook self-help style. But something she’d said about ambition was so clarifying and electrifying that I ended up buying the book to study what she was doing.

Now I know why Abrams wrote her book like this. After all, she could have written whatever kind of book she wanted. Her ambition is to have readers feel strong and capable enough to do whatever they put their minds to, whether it is to aid someone in office or be that person in office. She learned a lot on her path to this place and she doesn’t necessarily want to get to the top of the mountain without her cohort. Her ambition is not an office, it is a result.

What Abrams relates about her failures is most instructive. After all, none of us achieve all we set our minds to, at least on the first try. But Abrams shows that one has to be relentlessly honest with oneself about one’s advantages and deficiencies, even asking others in case one’s own interpretations are skewed by fear or previous failure. By writing her book this way, Abrams is unapologetic about some areas she could have handled better, personal finances for instance, that could have been used as a weapon against her. She explains her situation at the time and recommends better pathways for those who follow.

A former member of the Georgia State Legislature, Abrams found herself a different breed of politician than most who had achieved that rank. She was less attuned to social sway than she was to marshaling her intellect to overcome roadblocks to effective legislation. This undoubtedly had some genesis in the reactions she’d gotten her entire life as a black woman. She wasn’t going to wait for folks to accept her; she planned to take her earned seat at the table but she was going to be prepared.

She found that she needed both skills to succeed in business and in politics. She needed the support of a base and she needed an understanding of what would move the ball forward. And she learned what real power means.

If defeat is inevitable, reevaluate. Abrams suggests that one may need to change the rules of engagement so that instead of a ‘win’ one may be happy to ‘stay alive’ to fight another day.

The last fifty pages of the book put words to things we may know but haven’t articulated before. Abrams acknowledges that beliefs are anchors which help to direct us in decision-making but should never be used to block critical thinking, reasonable compromise, and thoughtful engagement.

It is difficult to believe there is anyone out there who doesn’t admire Stacey Abrams’ guts and perseverance. Her friends stood by her in times of stress because Abrams made efforts to acknowledge her weaknesses while not allowing them to break down her spirit. She built every pillar of the leadership role she talks about and can stand before us, challenging us to do the same. She is a powerhouse.

Tweet

Stacey Abrams learned to not always kick directly at her goal. Watching her stand back and assess a situation can be a fearsome thing. You know she is going to do something oh-so-effective and she is going to use her team to get there, those who mentored her and those she mentored herself. I just love that teamwork.

This memoir is unlike any other presidential-hopeful memoir out there. Abrams has not declared herself for the 2020 race, but running for president is on her to-do list. I read the library edition of her book quickly and wondered why she’d write it this way; she’s a writer and this is written in a workbook self-help style. But something she’d said about ambition was so clarifying and electrifying that I ended up buying the book to study what she was doing.

“Ambition should be an animation of soul…a disquiet that requires you to take action…Ambition means being proactive…If you can walk away [from your ambition] for days, weeks, or years at a time, it is not an ambition—it’s a wish.”Ambition is not something you can be passive about. You feel you must act on it or you will regret it all your days. Ambition should not a job title but something that helps you to answer “why”.

Now I know why Abrams wrote her book like this. After all, she could have written whatever kind of book she wanted. Her ambition is to have readers feel strong and capable enough to do whatever they put their minds to, whether it is to aid someone in office or be that person in office. She learned a lot on her path to this place and she doesn’t necessarily want to get to the top of the mountain without her cohort. Her ambition is not an office, it is a result.

What Abrams relates about her failures is most instructive. After all, none of us achieve all we set our minds to, at least on the first try. But Abrams shows that one has to be relentlessly honest with oneself about one’s advantages and deficiencies, even asking others in case one’s own interpretations are skewed by fear or previous failure. By writing her book this way, Abrams is unapologetic about some areas she could have handled better, personal finances for instance, that could have been used as a weapon against her. She explains her situation at the time and recommends better pathways for those who follow.

A former member of the Georgia State Legislature, Abrams found herself a different breed of politician than most who had achieved that rank. She was less attuned to social sway than she was to marshaling her intellect to overcome roadblocks to effective legislation. This undoubtedly had some genesis in the reactions she’d gotten her entire life as a black woman. She wasn’t going to wait for folks to accept her; she planned to take her earned seat at the table but she was going to be prepared.

She found that she needed both skills to succeed in business and in politics. She needed the support of a base and she needed an understanding of what would move the ball forward. And she learned what real power means.

“Access to real power also acknowledges that sometimes we need to collaborate rather than compete. We have to work with our least favorite colleague or with folks whose ideologies differ greatly from our own…But working together for a common end, if not for the same reason, means that more can be accomplished.”Abrams discusses strategies and tactics for acquiring and wielding power and reminds us that “sometimes winning takes longer than we hope” and leaders facing long odds on worthy goals best be prepared for the “slow-burn” where victory doesn’t arrive quickly. But every small victory or single act of defiance can inspire someone else to take action.

If defeat is inevitable, reevaluate. Abrams suggests that one may need to change the rules of engagement so that instead of a ‘win’ one may be happy to ‘stay alive’ to fight another day.

The last fifty pages of the book put words to things we may know but haven’t articulated before. Abrams acknowledges that beliefs are anchors which help to direct us in decision-making but should never be used to block critical thinking, reasonable compromise, and thoughtful engagement.

“Collaboration and compromise are necessary tools in gaining and holding power.”The GOP also believes this, but I think they use the notion within their coalition: they use discipline to keep their team in order and members may need to compromise their values to stay in the power group. Democrats must hold onto the notion of compromise within and without their coalition to succeed, while never compromising values.

It is difficult to believe there is anyone out there who doesn’t admire Stacey Abrams’ guts and perseverance. Her friends stood by her in times of stress because Abrams made efforts to acknowledge her weaknesses while not allowing them to break down her spirit. She built every pillar of the leadership role she talks about and can stand before us, challenging us to do the same. She is a powerhouse.

Tweet

Labels:

America,

government,

HH,

memoir,

nonfiction,

Picador,

politics,

race

Wednesday, March 27, 2019

Closer Than You Know by Brad Parks

Hardcover, 402 pgs, Pub March 6th 2018 by Dutton Books, ISBN13: 9781101985625

Brad Parks’ compulsively readable standalone crime thriller is nearly flawless. The author takes risks by making his protagonist a woman, a young white mother married to a black man. While he might make a misstep or two in how a woman might react to rape or a first-time mother might react to being wrongly accused of several crimes and then having her child taken by social services, he has a strong enough case that we keep reading to see how he will explain it all.

Technically, the book moves smoothly between points of view, from accused, to police, to perp, to innocent victim. Our own opinions are in flux as we get pushed and pulled with every new development in the case against the mother. She is a victim several times over, and we can explain her reticence to spill her guts and tell all she knows to her attorney by first considering her foster-care background.

The whole builds up to a situation in which good people can get hurt by other well-meaning people because everyone is being manipulated by normal human perceptions and reactions. Preet Bharara, former Chief Prosecutor for the Southern District of New York, recently wrote in his memoir that one thing he learned in his time at one of the most visible courts in the land that “[a]nyone is capable of anything.”

I read this book at first because the author is the son of one of my brother’s best friends, but I am pleased to be able to report that the skill, talent, and sheer dare-devil chutzpah of the author is on full display. Brad Parks takes risks but is able to pull off the heist. Congratulations, Brad Parks!

Tweet

Brad Parks’ compulsively readable standalone crime thriller is nearly flawless. The author takes risks by making his protagonist a woman, a young white mother married to a black man. While he might make a misstep or two in how a woman might react to rape or a first-time mother might react to being wrongly accused of several crimes and then having her child taken by social services, he has a strong enough case that we keep reading to see how he will explain it all.

Technically, the book moves smoothly between points of view, from accused, to police, to perp, to innocent victim. Our own opinions are in flux as we get pushed and pulled with every new development in the case against the mother. She is a victim several times over, and we can explain her reticence to spill her guts and tell all she knows to her attorney by first considering her foster-care background.

The whole builds up to a situation in which good people can get hurt by other well-meaning people because everyone is being manipulated by normal human perceptions and reactions. Preet Bharara, former Chief Prosecutor for the Southern District of New York, recently wrote in his memoir that one thing he learned in his time at one of the most visible courts in the land that “[a]nyone is capable of anything.”

I read this book at first because the author is the son of one of my brother’s best friends, but I am pleased to be able to report that the skill, talent, and sheer dare-devil chutzpah of the author is on full display. Brad Parks takes risks but is able to pull off the heist. Congratulations, Brad Parks!

Tweet

Friday, March 22, 2019

An Unlikely Journey by Julián Castro

Hardcover, 288 pgs, Pub Oct 16th 2018 by Little, Brown and Company, ISBN13: 9780316252164

Memoirs are de rigueur for anyone aspiring to the presidency. And so they should be, to introduce themselves and to give us an idea from where their sense of duty emanates. Nonetheless, it is disorienting to read the memoir of someone in their forties running for president who never mentions travel abroad.

At least half this book is composed of Julián’s life before he was twenty. For those who argue that “youthful indiscretions don’t matter,” here is someone who clearly thinks one’s sense of self and others grows up with you.

While I might go along with that notion of human development, it is the time after age twenty when we have to make decisions that really show who we are. After graduating from Stanford University and Harvard Law, Castro returned to his home city of San Antonio, took a job with a law firm and promptly ran for San Antonio City Council in his home district and won.

Right out of the gate was a big conflict of interest. Castro’s law firm represented a developer who wanted to build a golf course over the city’s aquifer and get a tax break to do it. Castro quit his paying job with the law firm, ended up voting no on the proposal with the backing of 56% of San Antonio residents.

The initial project failed--not because of his vote--but another came right behind it, this time for two golf courses, but with stronger environmental protections and no tax breaks. Castro voted for the project the second time. He uses the example of this project to show the importance of local government work, but also what people can do when they have principled objections and work together.

The experience fueled Castro’s interest in higher office. He lost at his first attempt to run for mayor of San Antonio, and it looks like it was his first big public failure. He felt humiliated. But like everyone who eventually succeeds, he had to pick himself up and do it again, which he did, winning in 2009. After that, he went back and forth to Washington, as head of HUD under Obama, and then mentioned as vice-presidential pick during the run up to the 2016 election.

It takes a special personality to want the blood sport that is politics. Castro learned the power of the people from his mother, who was known for her organizing work. He has a twin brother who absorbed the same lessons and worked alongside him to set up and win elections while they were in college and after. But what makes one reach for the highest office?

We all have to find the answer to that one, and while I am not impressed with those who want to see their names in lights—or gold letters eight feet high—there are people who are at least as capable as the rest of us but who want the limelight. I’m willing to give it to them if it makes sense for the direction we need to move.

Julián Castro is not ready, to my mind, to run for the presidency. I do not get the reassurance he even knows what it is. I don't mind some learning on the job, but look at what Teresa May just went through. There is a largeness to the job that will always exceed our best attempts to put our arms around it. Do I think he would be worthy some day? Maybe.

What we are doing now in our presidential slates--going as old as we can and as young as we can--is unappealing to me. Precociousness is a real thing, and I don't want to stand in the way of talent. To me, Castro for President is premature, but I have to admit the world belongs to the young now, who are going to have to find a way to live in it.

Tweet

Memoirs are de rigueur for anyone aspiring to the presidency. And so they should be, to introduce themselves and to give us an idea from where their sense of duty emanates. Nonetheless, it is disorienting to read the memoir of someone in their forties running for president who never mentions travel abroad.

At least half this book is composed of Julián’s life before he was twenty. For those who argue that “youthful indiscretions don’t matter,” here is someone who clearly thinks one’s sense of self and others grows up with you.

While I might go along with that notion of human development, it is the time after age twenty when we have to make decisions that really show who we are. After graduating from Stanford University and Harvard Law, Castro returned to his home city of San Antonio, took a job with a law firm and promptly ran for San Antonio City Council in his home district and won.

Right out of the gate was a big conflict of interest. Castro’s law firm represented a developer who wanted to build a golf course over the city’s aquifer and get a tax break to do it. Castro quit his paying job with the law firm, ended up voting no on the proposal with the backing of 56% of San Antonio residents.

The initial project failed--not because of his vote--but another came right behind it, this time for two golf courses, but with stronger environmental protections and no tax breaks. Castro voted for the project the second time. He uses the example of this project to show the importance of local government work, but also what people can do when they have principled objections and work together.

The experience fueled Castro’s interest in higher office. He lost at his first attempt to run for mayor of San Antonio, and it looks like it was his first big public failure. He felt humiliated. But like everyone who eventually succeeds, he had to pick himself up and do it again, which he did, winning in 2009. After that, he went back and forth to Washington, as head of HUD under Obama, and then mentioned as vice-presidential pick during the run up to the 2016 election.

It takes a special personality to want the blood sport that is politics. Castro learned the power of the people from his mother, who was known for her organizing work. He has a twin brother who absorbed the same lessons and worked alongside him to set up and win elections while they were in college and after. But what makes one reach for the highest office?

We all have to find the answer to that one, and while I am not impressed with those who want to see their names in lights—or gold letters eight feet high—there are people who are at least as capable as the rest of us but who want the limelight. I’m willing to give it to them if it makes sense for the direction we need to move.

Julián Castro is not ready, to my mind, to run for the presidency. I do not get the reassurance he even knows what it is. I don't mind some learning on the job, but look at what Teresa May just went through. There is a largeness to the job that will always exceed our best attempts to put our arms around it. Do I think he would be worthy some day? Maybe.

What we are doing now in our presidential slates--going as old as we can and as young as we can--is unappealing to me. Precociousness is a real thing, and I don't want to stand in the way of talent. To me, Castro for President is premature, but I have to admit the world belongs to the young now, who are going to have to find a way to live in it.

Tweet

Thursday, March 7, 2019

Washington Black by Esi Edugyan

Hardcover, 339 pgs,

Pub Sept 18th 2018 by Knopf Publishing Group (first pub August 2nd 2018), ISBN13: 9780525521426, Lit Awards: Man Booker Prize Nominee (2018), Scotiabank Giller Prize (2018), Governor General's Literary Awards / Prix littéraires du Gouverneur général Nominee for Fiction (2018), Andrew Carnegie Medal Nominee for Fiction (2019)

I finished Edugyan's third novel in a fog, reading the last hundred pages completely engrossed in the strange unreal world and story Edugyan had created, about a former slave, physically damaged from years in captivity but involved in the science of creating an indoor aquarium in London—something never done before.

If at first—and I have seen such criticism—the story seemed derivative of Jules Verne with wondrous and far-flung adventures, Edugyan pulled it off. There were wondrous adventures when naturalists and people of science began to turn their attention outside their own environments to the larger world. Anything they could conceive of was about to be tried…travel to the Arctic, say, or to the bottom of the ocean, or ballooning long distances. The story is an absolute feast of imagination.

Race is an important component of the story in that we have an abolitionist white scientist who chooses a young slave boy to be ballast for his balloon adventure. When the white master discovers his black ballast has exceptional drawing skills, the boy’s role changes. Though the two become close, there is always a power differential in their relationship that keeps the friendship from meaning as much to the white man as it does to the black man.

Edugyan sketches this kind of unconscious racism so clearly, and points to it, that one can hardly walk away from the book with one’s vision unchanged. We can put words to a feeling of distance or alienation we may have seen or felt before but weren’t able to express.

It turns out the history of the world’s first public aquarium is much as is described in this novel, though I was unable to discover whether a very young black man was the first to come up with the idea and design of the tanks for public display of sea creatures in the mid-nineteenth century. It seems perfectly likely, as does the fact that such a man would never be acknowledged, his history expunged as a matter of course.

Edugyan is Canadian, which is not obvious. She sets a portion of the novel in Newfoundland, but otherwise the characters travel far and wide on nearly every continent. She adds an intriguing love interest for George Washington Black, the main character and former slave from Barbados. We presume Black is originally from Dahoumey in west Africa because that place name is buried deep in his subconscious and is resurrected when his life is in danger.

Black’s love interest is a mixed-race island woman of great beauty and intelligence and a rounded sense of her own potential. Her father, also a scientist, did not encourage her to develop her physical charms. One day he allowed her to purchase a few small concessions to beauty that she craved: red lipstick, a diaphanous dress, an emerald clasp. She discovered that people noticed her more but saw her less. This lesson all women must learn and decide whether to exploit or not.

The start of the novel was not particularly convincing and had the feel of a young adult novel, but it began as it meant to go on, and by midway I was involved, suspending belief, rapt, curious. There was something about the way the role of the one-time slave was progressing that held some hope that his potential would be developed. And the history of race is not yet finished being told, since we write it every day.

It's a wonderful novel. Edugyan has written two other critically-acclaimed novels and at least two collections of stories. She has taught creative writing and has won several international awards for her work.

Tweet

I finished Edugyan's third novel in a fog, reading the last hundred pages completely engrossed in the strange unreal world and story Edugyan had created, about a former slave, physically damaged from years in captivity but involved in the science of creating an indoor aquarium in London—something never done before.

If at first—and I have seen such criticism—the story seemed derivative of Jules Verne with wondrous and far-flung adventures, Edugyan pulled it off. There were wondrous adventures when naturalists and people of science began to turn their attention outside their own environments to the larger world. Anything they could conceive of was about to be tried…travel to the Arctic, say, or to the bottom of the ocean, or ballooning long distances. The story is an absolute feast of imagination.

Race is an important component of the story in that we have an abolitionist white scientist who chooses a young slave boy to be ballast for his balloon adventure. When the white master discovers his black ballast has exceptional drawing skills, the boy’s role changes. Though the two become close, there is always a power differential in their relationship that keeps the friendship from meaning as much to the white man as it does to the black man.

Edugyan sketches this kind of unconscious racism so clearly, and points to it, that one can hardly walk away from the book with one’s vision unchanged. We can put words to a feeling of distance or alienation we may have seen or felt before but weren’t able to express.

It turns out the history of the world’s first public aquarium is much as is described in this novel, though I was unable to discover whether a very young black man was the first to come up with the idea and design of the tanks for public display of sea creatures in the mid-nineteenth century. It seems perfectly likely, as does the fact that such a man would never be acknowledged, his history expunged as a matter of course.

Edugyan is Canadian, which is not obvious. She sets a portion of the novel in Newfoundland, but otherwise the characters travel far and wide on nearly every continent. She adds an intriguing love interest for George Washington Black, the main character and former slave from Barbados. We presume Black is originally from Dahoumey in west Africa because that place name is buried deep in his subconscious and is resurrected when his life is in danger.

Black’s love interest is a mixed-race island woman of great beauty and intelligence and a rounded sense of her own potential. Her father, also a scientist, did not encourage her to develop her physical charms. One day he allowed her to purchase a few small concessions to beauty that she craved: red lipstick, a diaphanous dress, an emerald clasp. She discovered that people noticed her more but saw her less. This lesson all women must learn and decide whether to exploit or not.

The start of the novel was not particularly convincing and had the feel of a young adult novel, but it began as it meant to go on, and by midway I was involved, suspending belief, rapt, curious. There was something about the way the role of the one-time slave was progressing that held some hope that his potential would be developed. And the history of race is not yet finished being told, since we write it every day.

It's a wonderful novel. Edugyan has written two other critically-acclaimed novels and at least two collections of stories. She has taught creative writing and has won several international awards for her work.

Tweet

Labels:

Canada,

historical novel,

islands,

Knopf,

literature,

oceans,

race,

science

Friday, March 1, 2019

Becoming by Michelle Obama

Hardcover, 426 pgs, Pub Nov 13th 2018 by Crown, ISBN13: 978152476313, Lit Awards: Goodreads Choice Award Nominee for Memoir & Autobiography (2018)

Who would have guessed there would be two such popular and talented writers in one family as there are in the Obamas? I guess we will have to wait to see if their kids, Malia and Sasha, have inherited the gene. Michelle’s book is ravishingly interesting and so smoothly written I was happy sitting there and reading it at the neglect of less pleasurable duties.

The fairy-tale aspect of growing up “with a disabled dad in a too-small house with not much money in a starting-to-fail neighborhood” and ascending to the most admired and coveted house in the land is not emphasized until the last pages. Michelle looks back at Barack’s eight years in office, and how he was followed by a con man with a filthy mouth. The contrast between the two men is not subtle, and neither is Michelle’s distress.

Before the disappointing turnover at the end of Barack’s time in office, the story is filled with hope—hope that Americans will see change for the better in their opportunities, schooling, wages, and leadership. Michelle’s emphasis mostly stays squarely on her own hopes rather than those of her husband, and focuses on her plans to institute mentoring for teens of color, and the building of a system for providing good food for kids in schools.

Michelle made no bones about the fact that she was more a homebody than her cerebral husband who, in one anecdote, laid in bed late one night gazing at the ceiling. When asked what he was thinking about, he sheepishly answered, “income inequality.”

Michelle had come from a family that was large and loud and lived close by one another in Chicago. After claiming an undergraduate degree at Princeton, Michelle moved on to Harvard Law, taking advantage of the momentum. the opportunity, and the expectation that she would achieve what her parents did not. She may not have been timid, but she wasn’t exactly expansive in her view of herself or her life. She acknowledges Barack introduced her to a larger world with different but equally important personal and societal goals and expectations that are shared by millions.

I have seen in comments about this book that Michelle dodged important questions about Barack’s time in office that involved decisions the two of them would have made together, e.g., Reverend Wright, etc. and while her opinion may have added something to the narrative, I tend to agree with “write your own darn story” pushback. Michelle’s considered take on what it meant to her and her family when some people seemed to lay in wait to broadcast misinterpretations of her campaign stump speeches makes it clear we are lucky to get anything more. It is easy for us to forget Michelle was an actual surrogate for Barack. She had a heavy speechmaking schedule and drew such crowds that she finally scored a plane and a team of her own.

Probably the thing I am most impressed with—and what Michelle herself is most proud of—is her raising two consequential young girls in the fishbowl that is the White House. The girls survived, even thrived, in that place, and hopefully will have absorbed some of the grace and resilience of their parents. What we don’t know is what Michelle’s next act will be, for she is still a relatively young and IVy- trained lawyer. We know she doesn’t like politics, never has, but would still like to make a contribution.

Just having withstood the pressures of the White House without cracking and having taken the time to write a book that encourages others to see themselves as aspirants to national office is something to be thankful for. I am also grateful she provided the home life and support Barack needed in such a difficult job with such a difficult Congress. It wasn’t easy for either of them and in many ways it did not turn out as they had envisioned.

The Obamas could have had a more placid life without trying to handle affairs of state, so their attempt to share their strong family values was a kind of blessing. The book is a wonderfully smooth read (or audio!), and is hard-to-put-down. The audio is read by Michelle herself and therefore places the emphases where she wanted. Published by Crown and Random House Audio in North America, this book sold more copies in the U.S. than any other book in 2018 and will be published in 24 languages.

A section of color photographs is reason enough to choose the book over the audio, but the audio is interesting because Michelle herself reads it. She has chosen to discuss things we are intrinsically interested in, like choosing a college, a major, a job, and a husband, and while many of us have had similar decisions to make we would not have had Michelle’s set of choices. The book is absolutely worthwhile.

Tweet

Who would have guessed there would be two such popular and talented writers in one family as there are in the Obamas? I guess we will have to wait to see if their kids, Malia and Sasha, have inherited the gene. Michelle’s book is ravishingly interesting and so smoothly written I was happy sitting there and reading it at the neglect of less pleasurable duties.

The fairy-tale aspect of growing up “with a disabled dad in a too-small house with not much money in a starting-to-fail neighborhood” and ascending to the most admired and coveted house in the land is not emphasized until the last pages. Michelle looks back at Barack’s eight years in office, and how he was followed by a con man with a filthy mouth. The contrast between the two men is not subtle, and neither is Michelle’s distress.

Before the disappointing turnover at the end of Barack’s time in office, the story is filled with hope—hope that Americans will see change for the better in their opportunities, schooling, wages, and leadership. Michelle’s emphasis mostly stays squarely on her own hopes rather than those of her husband, and focuses on her plans to institute mentoring for teens of color, and the building of a system for providing good food for kids in schools.

Michelle made no bones about the fact that she was more a homebody than her cerebral husband who, in one anecdote, laid in bed late one night gazing at the ceiling. When asked what he was thinking about, he sheepishly answered, “income inequality.”

Michelle had come from a family that was large and loud and lived close by one another in Chicago. After claiming an undergraduate degree at Princeton, Michelle moved on to Harvard Law, taking advantage of the momentum. the opportunity, and the expectation that she would achieve what her parents did not. She may not have been timid, but she wasn’t exactly expansive in her view of herself or her life. She acknowledges Barack introduced her to a larger world with different but equally important personal and societal goals and expectations that are shared by millions.

I have seen in comments about this book that Michelle dodged important questions about Barack’s time in office that involved decisions the two of them would have made together, e.g., Reverend Wright, etc. and while her opinion may have added something to the narrative, I tend to agree with “write your own darn story” pushback. Michelle’s considered take on what it meant to her and her family when some people seemed to lay in wait to broadcast misinterpretations of her campaign stump speeches makes it clear we are lucky to get anything more. It is easy for us to forget Michelle was an actual surrogate for Barack. She had a heavy speechmaking schedule and drew such crowds that she finally scored a plane and a team of her own.

Probably the thing I am most impressed with—and what Michelle herself is most proud of—is her raising two consequential young girls in the fishbowl that is the White House. The girls survived, even thrived, in that place, and hopefully will have absorbed some of the grace and resilience of their parents. What we don’t know is what Michelle’s next act will be, for she is still a relatively young and IVy- trained lawyer. We know she doesn’t like politics, never has, but would still like to make a contribution.

Just having withstood the pressures of the White House without cracking and having taken the time to write a book that encourages others to see themselves as aspirants to national office is something to be thankful for. I am also grateful she provided the home life and support Barack needed in such a difficult job with such a difficult Congress. It wasn’t easy for either of them and in many ways it did not turn out as they had envisioned.

The Obamas could have had a more placid life without trying to handle affairs of state, so their attempt to share their strong family values was a kind of blessing. The book is a wonderfully smooth read (or audio!), and is hard-to-put-down. The audio is read by Michelle herself and therefore places the emphases where she wanted. Published by Crown and Random House Audio in North America, this book sold more copies in the U.S. than any other book in 2018 and will be published in 24 languages.

A section of color photographs is reason enough to choose the book over the audio, but the audio is interesting because Michelle herself reads it. She has chosen to discuss things we are intrinsically interested in, like choosing a college, a major, a job, and a husband, and while many of us have had similar decisions to make we would not have had Michelle’s set of choices. The book is absolutely worthwhile.

Tweet

Labels:

America,

Crown,

family,

government,

marriage,

memoir,

nonfiction,

politics,

race,

RH Audio

Thursday, February 21, 2019

Lake Success by Gary Shteyngart

Hardcover, 339 pgs, Pub Sept 4th 2018 by Random House, ISBN13: 9780812997415

I listened to this novel months ago—just about the time it came out. I haven’t been able to adequately put into words how I felt about it. This was the first time I’ve partaken of a Shteyngart novel, and it is more in every way than I was expecting. There is a shadow of Pynchon’s frank absurdity there, and some bungee-cord despair—the kind that bounces back, irrepressible.

Shteyngart’s novel is overstuffed with funny, sad, true, caustic, simplistic, derogatory observations about life in America that somehow capture us in all our glory. He is not dismissive; I think he likes us. The main character in this novel, Barry Cohen, is nothing if not representative of what we have taught ourselves to be: money-mad and self-pitying, educated enough to capture our own market but too stupid to see the big picture. What introspection we have is wasted on divining the motivations of others rather than our own triggers.

Barry is a man America loves to hate. He is a successful hedge fund manager who emerged from the economic crisis in fine shape—it was only his clients who suffered. And his clients suffered because the government finally caught on to some irregularities in Barry’s operations that allowed him to win so much. While the SEC investigated, Barry left Seema, his wife and an attorney, with his son Shiva to see if he could find an old flame. Last he’d heard she was living in the South.

Right there Barry made a big mistake. One doesn’t leave an attorney for another woman. I mean, how stupid do you have to be? Barry and Seema had been doing okay marriage-wise, though it turns out Shiva is autistic. Unable to speak and often looking as though he does not even comprehend what words and comments are directed to him, Shiva is unknowable.

Barry wants to love him, but maybe wants Shiva to love Barry himself more. Seema handles most of Shiva's care which means she cannot work. More and more absorbed with nurturing her son’s growth, she recognizes and relishes small victories in understanding Shiva's internal world while her husband languishes.

Barry Cohen’s odyssey from New York by bus to various destinations in the south features a man with a skill set that serves him surprisingly well when traveling by bus on limited cash, no credit, and a roller-board of fancy watches. He can’t be shamed because he’s a bigger crook than anyone. Dragging around his collection of fancy watches turns out not to be very lucrative—who recognizes their value? But they do get him food occasionally, and a little tradable currency.

Barry spends relatively little psychic energy pondering the sources of his Wall Street wealth, but somehow recognizes it’s probably not worth as much as he was getting paid to do it. His long-story-short gives us cameos of American ‘types’: street-wise salesmen, long-suffering nannies, practical mothers, and money managers who believe their work confers some kind of godliness on their financial outcomes. Because we win, we are meant to win. Yes, this all takes place in the first year of the Trump administration.

Barry Cohen is hard to take. “See, this is the thing about America,” he tells his former employee in Atlanta, a man named Park that Barry keeps referring to as Chinese, “You can never guess who’s going to turn out to be a nice person.”

Well. Barry is not a very nice person, really. He simply is not reflective enough. We can feel twinges at his angst, but ultimately we make our own beds, don’t we? Barry is tiresome, that’s the problem. His adventures are quite something, but we grow weary of his blind spots and slow recognition that he does, in fact, love his imperfect family. It’s all he’s got, the silly doofus, and they are worthy of his love. We’d rather spend time with them.

In an enlightening interview with The Guardian, Shteyngart acknowledges the story is about racism:

Tweet

I listened to this novel months ago—just about the time it came out. I haven’t been able to adequately put into words how I felt about it. This was the first time I’ve partaken of a Shteyngart novel, and it is more in every way than I was expecting. There is a shadow of Pynchon’s frank absurdity there, and some bungee-cord despair—the kind that bounces back, irrepressible.

Shteyngart’s novel is overstuffed with funny, sad, true, caustic, simplistic, derogatory observations about life in America that somehow capture us in all our glory. He is not dismissive; I think he likes us. The main character in this novel, Barry Cohen, is nothing if not representative of what we have taught ourselves to be: money-mad and self-pitying, educated enough to capture our own market but too stupid to see the big picture. What introspection we have is wasted on divining the motivations of others rather than our own triggers.

Barry is a man America loves to hate. He is a successful hedge fund manager who emerged from the economic crisis in fine shape—it was only his clients who suffered. And his clients suffered because the government finally caught on to some irregularities in Barry’s operations that allowed him to win so much. While the SEC investigated, Barry left Seema, his wife and an attorney, with his son Shiva to see if he could find an old flame. Last he’d heard she was living in the South.

Right there Barry made a big mistake. One doesn’t leave an attorney for another woman. I mean, how stupid do you have to be? Barry and Seema had been doing okay marriage-wise, though it turns out Shiva is autistic. Unable to speak and often looking as though he does not even comprehend what words and comments are directed to him, Shiva is unknowable.

Barry wants to love him, but maybe wants Shiva to love Barry himself more. Seema handles most of Shiva's care which means she cannot work. More and more absorbed with nurturing her son’s growth, she recognizes and relishes small victories in understanding Shiva's internal world while her husband languishes.

Barry Cohen’s odyssey from New York by bus to various destinations in the south features a man with a skill set that serves him surprisingly well when traveling by bus on limited cash, no credit, and a roller-board of fancy watches. He can’t be shamed because he’s a bigger crook than anyone. Dragging around his collection of fancy watches turns out not to be very lucrative—who recognizes their value? But they do get him food occasionally, and a little tradable currency.

Barry spends relatively little psychic energy pondering the sources of his Wall Street wealth, but somehow recognizes it’s probably not worth as much as he was getting paid to do it. His long-story-short gives us cameos of American ‘types’: street-wise salesmen, long-suffering nannies, practical mothers, and money managers who believe their work confers some kind of godliness on their financial outcomes. Because we win, we are meant to win. Yes, this all takes place in the first year of the Trump administration.

Barry Cohen is hard to take. “See, this is the thing about America,” he tells his former employee in Atlanta, a man named Park that Barry keeps referring to as Chinese, “You can never guess who’s going to turn out to be a nice person.”

Well. Barry is not a very nice person, really. He simply is not reflective enough. We can feel twinges at his angst, but ultimately we make our own beds, don’t we? Barry is tiresome, that’s the problem. His adventures are quite something, but we grow weary of his blind spots and slow recognition that he does, in fact, love his imperfect family. It’s all he’s got, the silly doofus, and they are worthy of his love. We’d rather spend time with them.

In an enlightening interview with The Guardian, Shteyngart acknowledges the story is about racism:

"I think racism undergirds all of this, no question. It’s a huge part of it. When we were immigrants and couldn’t speak the language, the one thing this country told us was: ‘You’re white, there’s always somebody lower than you.’"Shteyngart thought he might add a gender dimension to the story, and was going to make his main character a woman, but the few female hedge fund managers he found were rational and didn’t take such big crazy risks that they end up blowing up the world. Right, I think. Exactly right.

Tweet

Tuesday, February 19, 2019

Friday Black: Stories by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

Paperback, 194 pgs, Pub Oct 23rd 2018 by Mariner Books, ISBN13: 9781328911247, Lit Awards: Dylan Thomas Prize Nominee for Longlist (2019), Aspen Words Literary Prize Nominee for Longlist (2019)

I forget where I first heard of Adjei-Brenyah, but it was about the time of publication in 2018 and the name of his debut story collection was so similar to Esi Edugyan’s much-lauded Washington Black that I wanted to read both to make sure they were separated in my mind. Now it is difficult to imagine I would ever forget the title story “Friday Black,” about a young man in a retail store setting dealing with the sales and buying mania of Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving and the official opening of the Christmas season. There is indeed something black in the American psyche, that would celebrate a day of such whipped-up and fruitless passion for more than we need or can effectively use.

I did not read the first story in the collection, “The Finkelstein 5,” until long into my perusal of the collection. Just as well, because it stares full-face into the racism we still see and hear all around us today. The characters who are black attempt to fit into white society, dialling up or down their overt display of “blackness” on a ten-point scale they believe the white overculture has created for them.

Adjei-Brenyah draws from the incidental murders of young girls attending Sunday school, of a young man shot as he walked down the night-darkened street of his neighborhood, of a young man so angry at the deaths of the others that he considers, for a moment, fighting back. There is a barely-disguised cameo of the talking heads on right-wing TV talk shows, with Adjei-Brenyah carefully picking out for us the most offensive and patently absurd of their comments regarding white fear of unarmed teens and children of color.

My favorite of the stories in the collection has to be “Zimmer Land.” In this significant piece, which I can imagine being chosen for Best-Of collections until Adjei-Brenyah is old and gray, a young man works at a kind of play-station where members of the community are given the opportunity to see how they would react when their fear or anger instincts are aroused.

Patrons are issued a weapon when they enter the play space set, a paint gun whose force can rupture fake blood sensors in the mecha-suit of the player. Mecha-suits sound like transformer kits, inflating to protect the torso, legs, and arms of players, and to intimidate patrons. Patrons are not told to use the weapons they are issued, but the mere convenience of the weapons is an opportunity, and the rush of shooting is like a fast-acting drug.

Isaiah is black and he is the player white patrons come to test their emotions against in a “highly curated environment.” When Isaiah complains to management that most of the patrons are repeats, coming frequently to fake-kill him and not learning anything new about the sources of their aggression, perhaps even “equating killing with justice,” his bosses tell him his heart better be in the job ‘cause there are others who’ll do the work with real aggression and commitment.

At least four of Adjei-Brenyah’s signature pieces in this collection describe the soul-destroying unreality of America’s retail space, where salespeople are rewarded for up-selling and given praise, if not bonuses, for selling the most [unnecessary] stuff to the most [psychically- or financially-vulnerable] people. We are reminded that there are several ways to make money while hoping to make a living writing, and in Adjei-Brenyah’s case it is retail sales rather than, say, restaurant work or construction. He gives us a look at what we never thought to ask as we made our way through the racks of shirts or stacks of jeans.

Highly praised by other acclaimed writers in front-page and back-cover blurbs, this collection heralds the arrival of someone we will continue to look out for. The ideas behind the work is what is impressive, besides just the writing skill. Adjei-Brenyah knows one doesn’t have to be sky-diving to make the work interesting. It’s about what you’re thinking about while sky-diving.

Late Night comedian Seth Meyers interviews Adjei-Brenyah about this collection:

Book Riot interviewed Adjei-Brenyah and one set of paragraphs stood out:

Tweet

I forget where I first heard of Adjei-Brenyah, but it was about the time of publication in 2018 and the name of his debut story collection was so similar to Esi Edugyan’s much-lauded Washington Black that I wanted to read both to make sure they were separated in my mind. Now it is difficult to imagine I would ever forget the title story “Friday Black,” about a young man in a retail store setting dealing with the sales and buying mania of Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving and the official opening of the Christmas season. There is indeed something black in the American psyche, that would celebrate a day of such whipped-up and fruitless passion for more than we need or can effectively use.

I did not read the first story in the collection, “The Finkelstein 5,” until long into my perusal of the collection. Just as well, because it stares full-face into the racism we still see and hear all around us today. The characters who are black attempt to fit into white society, dialling up or down their overt display of “blackness” on a ten-point scale they believe the white overculture has created for them.

Adjei-Brenyah draws from the incidental murders of young girls attending Sunday school, of a young man shot as he walked down the night-darkened street of his neighborhood, of a young man so angry at the deaths of the others that he considers, for a moment, fighting back. There is a barely-disguised cameo of the talking heads on right-wing TV talk shows, with Adjei-Brenyah carefully picking out for us the most offensive and patently absurd of their comments regarding white fear of unarmed teens and children of color.

My favorite of the stories in the collection has to be “Zimmer Land.” In this significant piece, which I can imagine being chosen for Best-Of collections until Adjei-Brenyah is old and gray, a young man works at a kind of play-station where members of the community are given the opportunity to see how they would react when their fear or anger instincts are aroused.

Patrons are issued a weapon when they enter the play space set, a paint gun whose force can rupture fake blood sensors in the mecha-suit of the player. Mecha-suits sound like transformer kits, inflating to protect the torso, legs, and arms of players, and to intimidate patrons. Patrons are not told to use the weapons they are issued, but the mere convenience of the weapons is an opportunity, and the rush of shooting is like a fast-acting drug.

Isaiah is black and he is the player white patrons come to test their emotions against in a “highly curated environment.” When Isaiah complains to management that most of the patrons are repeats, coming frequently to fake-kill him and not learning anything new about the sources of their aggression, perhaps even “equating killing with justice,” his bosses tell him his heart better be in the job ‘cause there are others who’ll do the work with real aggression and commitment.

At least four of Adjei-Brenyah’s signature pieces in this collection describe the soul-destroying unreality of America’s retail space, where salespeople are rewarded for up-selling and given praise, if not bonuses, for selling the most [unnecessary] stuff to the most [psychically- or financially-vulnerable] people. We are reminded that there are several ways to make money while hoping to make a living writing, and in Adjei-Brenyah’s case it is retail sales rather than, say, restaurant work or construction. He gives us a look at what we never thought to ask as we made our way through the racks of shirts or stacks of jeans.

Highly praised by other acclaimed writers in front-page and back-cover blurbs, this collection heralds the arrival of someone we will continue to look out for. The ideas behind the work is what is impressive, besides just the writing skill. Adjei-Brenyah knows one doesn’t have to be sky-diving to make the work interesting. It’s about what you’re thinking about while sky-diving.

Late Night comedian Seth Meyers interviews Adjei-Brenyah about this collection:

Book Riot interviewed Adjei-Brenyah and one set of paragraphs stood out:

EM: Reading this collection, I could really feel a lot of non-literary influences in your writing. Like maybe a little bit of cinema and television crept in there as well.

NKAB: Yeah.

EM: Could you talk more specifically about what some of those influences were?

NKAB: Yeah, I grew up reading a lot of serial sci-fi and fantasy. I read Animorphs as a kid. I’m from the Harry Potter generation. But outside of books and stuff, I love anime, from Dragonball-Z to more cerebral stuff like Death Note or this anime called Monster. Miyazaki stuff as well. And what’s cool about that is I was made to view those things as valid for a lot of high-level thought. It’s funny because when you see parodies of anime, there will be people in the middle of fights having really philosophical debates. Anime is really big on that, and that was important to me. When there’s violence, it’s very much couched in “this is why,” and that rubbed off on me, I think.”

Tweet

Friday, September 14, 2018

Night Sky with Exit Wounds by Ocean Vuong

Paperback, 89 pgs, Pub April 5th 2016 by Copper Canyon Press, ISBN 155659495X, Lit Awards: T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry (2018), Forward Prize for Best First Collection (2017), Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry (2017), Goodreads Choice Award Nominee for Poetry (2016)

Published in 2016, this is Ocean Vuong’s first full collection. We will never know how a boy emerges, so young, with a talent so great. A poem chosen at random lights deep, protected nodes in our brain and attaches to our viscera. We recognize his work as surely as we appreciate a painting, or a piece of music. He appears a conduit, not a creator.

One of the poems in this collection has a title referencing a Mark Rothko painting. Glancing at it, we know immediately why he pairs it with these words.

In an interview with The Guardian, Vuong says “life is always more complicated than the headlines allow; poetry comes in when the news is not enough.” Vuong won awards for this collection, and gained recognition. He now is an associate professor in the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and writing a novel.

In an interview with Lit Hub Vuong explains

Vuong’s poetry is available as an ebook from many libraries. He is what we call a ‘literary light.’

Tweet

Published in 2016, this is Ocean Vuong’s first full collection. We will never know how a boy emerges, so young, with a talent so great. A poem chosen at random lights deep, protected nodes in our brain and attaches to our viscera. We recognize his work as surely as we appreciate a painting, or a piece of music. He appears a conduit, not a creator.

One of the poems in this collection has a title referencing a Mark Rothko painting. Glancing at it, we know immediately why he pairs it with these words.

Untitled (Blue, Green, and Brown, 1952)Rothko's Blue, Green, and Brown, 1952 It was the phrase How we live like water: wetting a new tongue with no telling what we've been through. That phrase stopped me.

The TV said the planes have hit the buildings.

& I said Yes because you asked me

to stay. Maybe we pray on our knees because god

only listens when we're this close

to the devil. There is so much I want to tell you.

How my greatest accolade was to walk

across the Brooklyn Bridge

& not think of flight. How we live like water: wetting

a new tongue with no telling

what we've been through. They say the sky is blue

but I know it's black seen through too much distance.

You will always remember what you were doing

when it hurts the most. There is so much

I need to tell you--but I only earned

one life & I took nothing. Nothing. Like a pair of teeth

at the end. The TV kept saying The planes...

The planes... & I stood waiting in the room

made of broken mockingbirds. Their wings throbbing

into four blurred walls. & you were there.

You were the window.

In an interview with The Guardian, Vuong says “life is always more complicated than the headlines allow; poetry comes in when the news is not enough.” Vuong won awards for this collection, and gained recognition. He now is an associate professor in the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and writing a novel.

In an interview with Lit Hub Vuong explains

“I’m writing a novel composed of woven inter-genre fragments. To me, a book made entirely out of unbridged fractures feels most faithful to the physical and psychological displacement I experience as a human being. I’m interested in a novel that consciously rejects the notion that something has to be whole in order to tell a complete story. I also want to interrogate the arbitrary measurements of a “successful” literary work, particularly as it relates to canonical Western values. For example, we traditionally privilege congruency and balance in fiction, we want our themes linked, our conflicts “resolved,” and our plots “ironed out.” But when one arrives at the page through colonized, plundered, and erased histories and diasporas, to write a smooth and cohesive novel is to ultimately write a lie.”Vuong brings with him the possibility of a vision that is articulate enough to share, brave enough to bolster. It's a kind of blessing, a grace note we don't really deserve, his voice.

Vuong’s poetry is available as an ebook from many libraries. He is what we call a ‘literary light.’

Tweet

Labels:

America,

Asia,

Copper Canyon Press,

family,

nonfiction,

poetry,

race,

sexuality

Tuesday, August 28, 2018

Jackrabbit Smile & Edge of Dark Water by Joe Lansdale

Hardcover, 256 pgs, Pub March 27th 2018 by Mulholland Books, ISBN13: 9780316311588, Series: Hap and Leonard #12

The Hal & Leonard series is full up with crazy male bravado and vulnerability, pressing hard on our moral, sexual, and racial understanding until we squeeze out a guffaw and decide to fall for these guys sitting on our faces. These two take on challenges others would let fall into a fast-flowing river, and now that the series has become a regular gig on Sundance Channel as an Original Series, starring America’s own brilliant, tough-seeming, and comedic Michael Kenneth Williams and British star James Purefoy, hopefully Joe Lansdale will get more airtime .

Lansdale barrels ahead riding roughshod over anyone who hasn’t updated their hard drive with new information about the lives of gays, trans, and people of color. No more excuses will be made for those faltering on the road to total acceptance of these folks living in America. Lansdale doesn’t make any bones about it, just assumes the bad guys are the unreformed who ‘haven’t quite gotten there yet.’ There is damage being done daily to the psyches of ordinary folk with extraordinary skills who have to put up with crippling prejudice.

This fast-paced addition to the series addresses white supremacy head on: WHITE IS RIGHT is emblazoned on the T-shirt of a young man seeking the investigative services of Hap & Leonard, not knowing Leonard can be rattlesnake mean to those who disparage him for his color...or any old thing he might take it in his mind to do. This is the book #12 in the series so Lansdale doesn’t spend much time explaining the two main characters. The chapters are short and speedy, racing to a gruesome dénouement that features a hog farm, some mean twins, and a jackrabbit smile.

This is the kind of book one can read in a day, relaxedly, since it is mainly composed of dialogue and a few hard whacks of a rifle butt. But it will put you in a good mood since the bad guys get theirs and the good guys, well, they may not ever get paid, but think of what they’re doing for the planet! I ❤️ Joe Lansdale.

------------------ -

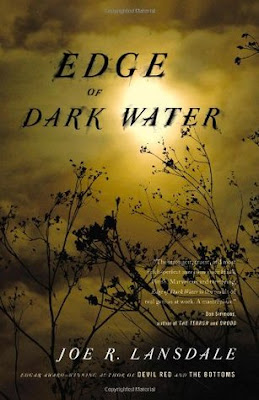

Hardcover, 292 pgs, Pub Mar 27th 2012 by Mulholland Books, ISBN13: 9780316188432

Is there a more prolific writer of Westerns than Joe Lansdale? Endlessly inventive, Lansdale has both a series featuring Hap & Leonard, and a slew of standalones in which he shares the way even good people can get themselves in a bad way in a world with evil in it.

In this standalone novel, published in 2012 by Mulholland Books, 16-year-old Sue Ellen is narrating. She lives in a small southern town and has two friends her age: a white gay boy named Terry who is reluctant to let anyone know his inclinations, and Jinx, a black girl friend since childhood. Lansdale is so natural in his use of skin color that he can teach us things we never knew we needed to know.

Sue Ellen, Terry, and Jinx discover the town’s beauty, May Lynn, killed and submerged in the river, tied by the ankle with wire attached to a sewing machine. None of the grown men in the town seem to want to pursue the matter, but merely shove the body in a casket and cover up the evidence. We get a bad feeling, but mostly we sense any sixteen-year-olds ought to pack up & leave that place, so when the kids decide that’s what they’re going to do, we’re onboard.

They’re floating, by the way, on a wooden raft, and along the way they pick up more than one who decides to go with them. Seems like practically everyone who knows their plans—to go to Hollywood—wants to go with them, if not the whole way, at least far enough to get out of town. There’s a posse of folks, more than one, following behind, looking for them, so it gets hectic and dangerous and the hangers-on fall off, one by one.

Lansdale always seems to get the tone right, however, and when there is a chance for evil to thrive he makes us question whether or not that’s the way we want things to play out. After all this is kind of a crime novel, kind of a police procedural, kind of a mystery, but it’s got heart…more heart than we’ve come to expect of the genre. I like the way people think and make choices that seem fair and right and good.

Lansdale himself is really kind of a standalone guy. As far as I know there isn’t anyone else doing this kind of crossover writing with lessons on race, human nature, and on right and wrong. It is never sappy, often funny, and always deeply thoughtful. He is not religious: “I got misery enough in my life without adding religion to it,” says a character in one of his later novels. The language he uses is country, and can be extremely descriptive, if not entirely proper: “Expectations is a little like fat birds—it’s better to kill them in case they flew away” or “certain feelings rose to the surface like dead carp.”

The Hap & Leonard series has been made into a TV series starring Michael Kenneth Williams and James Purefoy. It is a rich stew of southern storytelling, darkened by reality but leavened with laughter. I don’t think I need to state how difficult it is to create new characters, new language, and new situations every year (sometimes more than once a year? is it possible?) and hit the bell each time. I’m a fan.

Tweet

The Hal & Leonard series is full up with crazy male bravado and vulnerability, pressing hard on our moral, sexual, and racial understanding until we squeeze out a guffaw and decide to fall for these guys sitting on our faces. These two take on challenges others would let fall into a fast-flowing river, and now that the series has become a regular gig on Sundance Channel as an Original Series, starring America’s own brilliant, tough-seeming, and comedic Michael Kenneth Williams and British star James Purefoy, hopefully Joe Lansdale will get more airtime .

Lansdale barrels ahead riding roughshod over anyone who hasn’t updated their hard drive with new information about the lives of gays, trans, and people of color. No more excuses will be made for those faltering on the road to total acceptance of these folks living in America. Lansdale doesn’t make any bones about it, just assumes the bad guys are the unreformed who ‘haven’t quite gotten there yet.’ There is damage being done daily to the psyches of ordinary folk with extraordinary skills who have to put up with crippling prejudice.

This fast-paced addition to the series addresses white supremacy head on: WHITE IS RIGHT is emblazoned on the T-shirt of a young man seeking the investigative services of Hap & Leonard, not knowing Leonard can be rattlesnake mean to those who disparage him for his color...or any old thing he might take it in his mind to do. This is the book #12 in the series so Lansdale doesn’t spend much time explaining the two main characters. The chapters are short and speedy, racing to a gruesome dénouement that features a hog farm, some mean twins, and a jackrabbit smile.

This is the kind of book one can read in a day, relaxedly, since it is mainly composed of dialogue and a few hard whacks of a rifle butt. But it will put you in a good mood since the bad guys get theirs and the good guys, well, they may not ever get paid, but think of what they’re doing for the planet! I ❤️ Joe Lansdale.

------------------ -

Hardcover, 292 pgs, Pub Mar 27th 2012 by Mulholland Books, ISBN13: 9780316188432

Is there a more prolific writer of Westerns than Joe Lansdale? Endlessly inventive, Lansdale has both a series featuring Hap & Leonard, and a slew of standalones in which he shares the way even good people can get themselves in a bad way in a world with evil in it.

In this standalone novel, published in 2012 by Mulholland Books, 16-year-old Sue Ellen is narrating. She lives in a small southern town and has two friends her age: a white gay boy named Terry who is reluctant to let anyone know his inclinations, and Jinx, a black girl friend since childhood. Lansdale is so natural in his use of skin color that he can teach us things we never knew we needed to know.

Sue Ellen, Terry, and Jinx discover the town’s beauty, May Lynn, killed and submerged in the river, tied by the ankle with wire attached to a sewing machine. None of the grown men in the town seem to want to pursue the matter, but merely shove the body in a casket and cover up the evidence. We get a bad feeling, but mostly we sense any sixteen-year-olds ought to pack up & leave that place, so when the kids decide that’s what they’re going to do, we’re onboard.

They’re floating, by the way, on a wooden raft, and along the way they pick up more than one who decides to go with them. Seems like practically everyone who knows their plans—to go to Hollywood—wants to go with them, if not the whole way, at least far enough to get out of town. There’s a posse of folks, more than one, following behind, looking for them, so it gets hectic and dangerous and the hangers-on fall off, one by one.

Lansdale always seems to get the tone right, however, and when there is a chance for evil to thrive he makes us question whether or not that’s the way we want things to play out. After all this is kind of a crime novel, kind of a police procedural, kind of a mystery, but it’s got heart…more heart than we’ve come to expect of the genre. I like the way people think and make choices that seem fair and right and good.

Lansdale himself is really kind of a standalone guy. As far as I know there isn’t anyone else doing this kind of crossover writing with lessons on race, human nature, and on right and wrong. It is never sappy, often funny, and always deeply thoughtful. He is not religious: “I got misery enough in my life without adding religion to it,” says a character in one of his later novels. The language he uses is country, and can be extremely descriptive, if not entirely proper: “Expectations is a little like fat birds—it’s better to kill them in case they flew away” or “certain feelings rose to the surface like dead carp.”

The Hap & Leonard series has been made into a TV series starring Michael Kenneth Williams and James Purefoy. It is a rich stew of southern storytelling, darkened by reality but leavened with laughter. I don’t think I need to state how difficult it is to create new characters, new language, and new situations every year (sometimes more than once a year? is it possible?) and hit the bell each time. I’m a fan.

Tweet

Friday, August 3, 2018

White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo

Paperback, 192 pgs, Pub June 26th 2018 by Beacon Press, ISBN13: 9780807047415

The provocative title of this book is a draw. What are we doing, saying, and thinking that is unconscious and yet still brings out some kind of anger or fear response in us when challenged? I am constantly learning how much I don’t know about race in America and much more there is to know. DiAngelo is also white, by the way. She, too, makes racist mistakes, though more rarely now, even years after immersing herself in how it manifests. We can’t escape it. We have to acknowledge it.

That is basically what this book is about. How we must acknowledge our race, that we do in fact see race, that we make assumptions about people based on race, how we need to disrupt habitual patterns of interaction, and then consciously try to put ourselves in the way of disrupting the patterns of racism which are literally claiming the lives of too many people of color for reasons we would never recognize as legitimate in our own lives. It’s been, give or take, one hundred and fifty years since the Civil War. Sometimes it feels as it hasn’t been won by anti-slavers. Shame on us.