Has an Irishman written the Great American Novel? The question is not theoretical; Sebastian Barry’s latest novel is the fourth time he has been longlisted for the Man Booker Prize. It is his seventh, but it doesn't have the density of a novel. It is Barry’s long experience writing for the theatre—thirteen plays already—that lends excitement to this work. After the years of excellent effort, suddenly Thomas McNulty springs full-grown from Barry’s well-tilled field. The success of this gem of a novel set in 1850’s America is all about preparedness and inspiration.

The novel is not long but is fluent and unstrained; it makes big statements about human existence, war, love, about what we want, and what we get. It is remarkable how squarely Barry lands in the middle of the American debate so clamorous around us now, about race, diversity, sexuality, what we fight for and who fights for us—questions we’ve never satisfactorily answered.

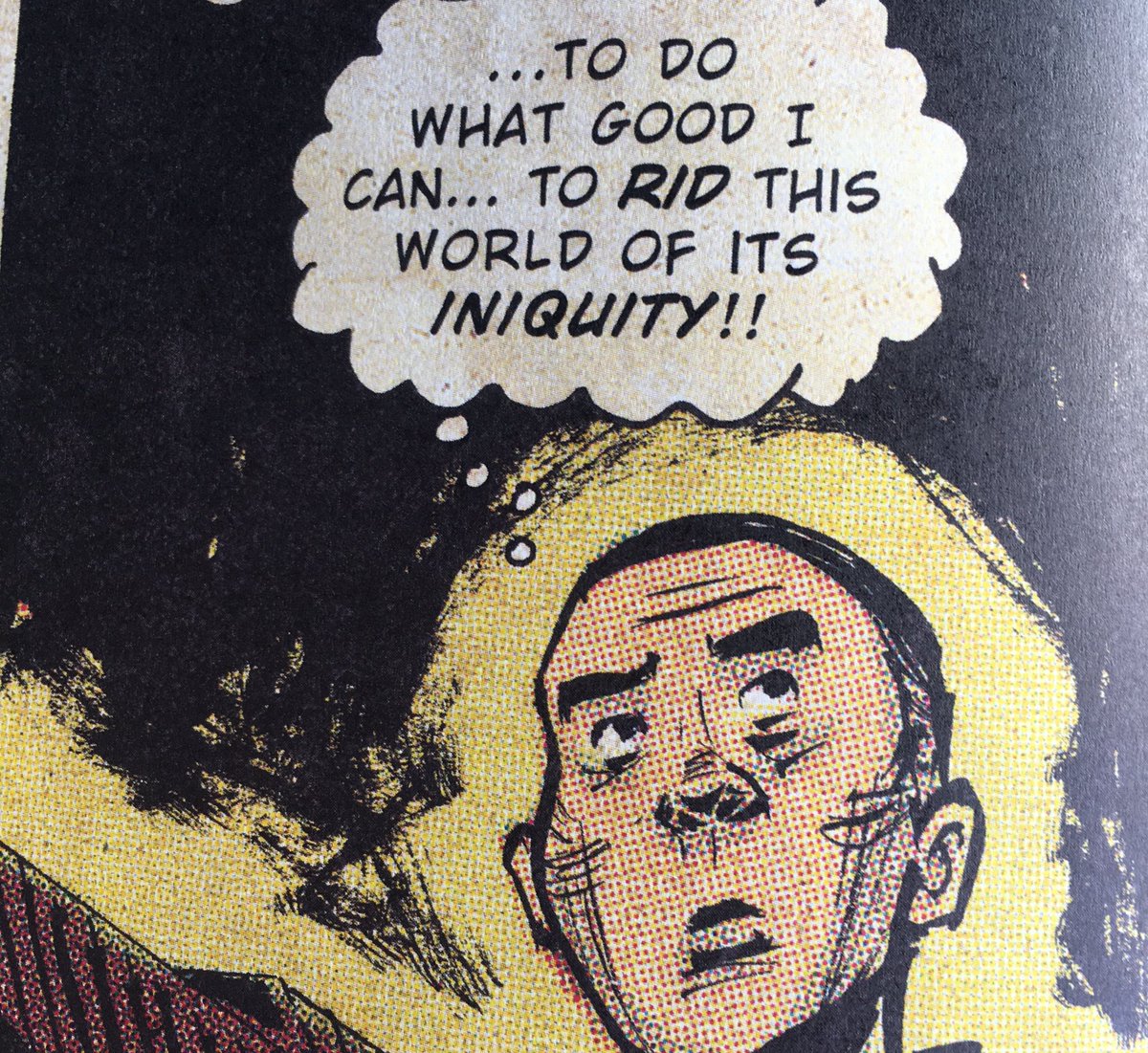

Barry gives us humor in a horribly violent world, surprising and delighting us with his deadpan delivery. His diverse cast of characters are reliant on one another, all viewed through the eyes of an Irishman who’d suffered such terrible deprivations as a child that man’s cruelty nevermore surprised him. What did surprise him was that we could find a way to love, to happiness, despite our sorrows.

In the early pages Thomas McNulty meets John Cole under a hedge in a rainstorm. John Cole is a few years older, but both the orphaned boys are wild things, having ‘growed' in the school of hard knocks. Uncanny judges of character, they almost instantly decide they stand a better chance together in the rough-and-tumble than alone and set off on a series of adventures. The pace of the novel is swift. When I go back to find a memorable passage, I am shocked at how quickly events unfolded, and how quickly I am deeply involved.

The language is one of the novel's wonders. Barry doesn’t try to hide his brogue, but uses it: a stranger in a strange land. That distance and perspective allows Thomas to make comment upon what is commonly observed

"Everything bad gets shot in America, says John Cole, and everything good too."and

"I know I can rely on the kindness of folk along the way. The ones that don’t try to rob me will feed me. That how it is in America."The novel constantly surprises: when the boys answer the ad hung awry on a saloon door in a broken-down Kansas town, “Clean Boys Wanted,” we prepare for the worst. Within pages we are jolly and laughing, then agonized and pained, then back again, our emotions rocketing despite the tamped-down telling of the historical backward gaze. Our initial sense of extreme danger never really leaves us, but serves to prepare us for the Indian wars, those pitiful, personal slaughters, and the Civil War, which comes soon enough.

The most remarkable bits of this novel, the sense of a shared humanity within a wide diversity, seemed so natural and obvious and wonderful we wanted to crawl under that umbrella and shelter there. These fierce fighting men fought for each other rather than for an ideal. Their early lives were so precarious they’d formed alliances across race, religion, national origin when they were treated fair. “Don’t tell me a Irish is an example of civilised humanity…you‘re talking to two when you talk to one Irishman.”

And then there is the notion of time, if it is perceived at all by youth: “Time was not something then we thought of as an item that possessed an ending…” By the end of the novel, the characters do indeed perceive time: “I am doing that now as I write these words in Tennessee. I am thinking of the days without end of my life. And it is not like that now.” We have been changed, too, because we also perceive time, and sorrow and pain and those things that constitute joy. We have lived his life, and ours, too.

Barry gets so much right about the America he describes: the sun coming up earlier and earlier as one travels east, the desert-but-not-desert plains land, the generosity and occasional cooperation between the Indian tribes and the army come to dispatch them, the crazy deep thoughtless racism. But what made me catch my breath with wonder was the naturalness of the union between

Barry understands absolutely that our diversity makes us stronger, better men. Leave the pinched and hateful exclusion of differentness to sectarian tribes, fighting for the old days. We know what the old days were like. We can do better. I haven’t read all the Man Booker longlist yet but most, and this is at the top of my list. It is a treasure.

I had access to the Viking Penguin hardcopy of this novel--I'm still surprised at how small it is, given the expansive nature of the story--but I also had the audio from Hoopla. I needed both: the pace of the novel is swift, and may cause us to read faster than we ought. Barry writes poetically, which by rights should slow us down. The Blackstone Audio production, though read quickly by Aidan Kelly, allows us to catch things we will have missed in print and vice versa. At several stages in this novel, crises impel us forward. As we rush to see what happens, we may miss the beauty. Don't miss the beauty. Books like these are so very rare.

You can buy this book here:

Tweet

Tweet