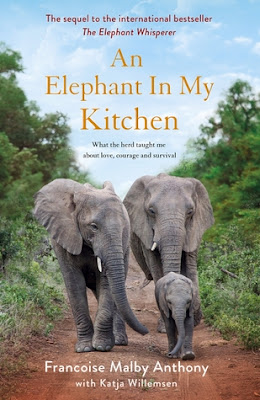

Hardcover, 336 pgs, Expected pub: Nov 5th 2019 by Thomas Dunne Books (first pub June 13th 2019), ISBN13: 9781250220141

For those who find animal emotions and inter-species friendships absorbing, this is a wonderful story about the ways rhinos, hippos, and elephants connect with each other and with humans.

Françoise Malay-Anthony was wife to the original Elephant Whisperer himself, Lawrence Anthony, who wrote a book of that name with famed nature-writer Graham Spence about his experiences creating an animal preserve in South Africa, called Thula Thula. At first Thula Thula was simply a preserve for herds of elephants whose habitat was disappearing. Soon it became apparent that poaching of elephant tusks and rhino horns was leaving vulnerable and traumatized babies to fend for themselves in dangerous territory.

Thula Thula gradually became known for emergency treatment of large animals prematurely separated from their mothers. A dedicated team of young volunteers from around the world worked hard to save endangered rhinos and baby elephants abandoned by their herd.

Leadership for this turn in the direction of Thula Thula, also a game reserve with hotel and bush drives for tourists to bring in money, came at the instigation of Françoise Malby-Anthony after the death of her husband, a time when she was anxious about managing the property without the extraordinary skills her husband possessed.

We learn of her vulnerability in light of world-class scam artists who sought to divert from her goal to make the environment better for animals in the wild. Her education in the ways of the wild—the wild world of tusk and horn poaching—is painful.

The viciousness of poaching by unscrupulous actors with enormous cash reserves has changed the entire focus of those in Africa seeking to preserve large animal habitat and populations. Trained security has had to devise ingenious methods of divining poachers plans and methods. This change in focus from trying to create a nurturing environment to defending territory and wildlife against indescribable violence is a disheartening change and a difficult way to live.

Compare those horrors with a young male elephant seeking the limelight—turning his rump to a jeep full of camera-toting watchers and twerking for the crowd. And an exploration of the character of rhino surprises readers utterly for what it tells us of their fearfulness and gentleness.

We likewise meet a hippo initially very suspicious of being asked to step into a green wading pool with a scant amount of water. We meet the handlers who become these distressed animals’ best buddies, teaching them to play despite their trauma, and protecting them as best they can from the nightmares that plague them.

If readers enjoy the stories in this book, one absolutely must make an attempt to locate a copy of The Elephant Whisperer referenced above because of what it adds in richness to the story and the description of the environment and told by a world-class raconteur.

Tweet

Showing posts with label memoir. Show all posts

Showing posts with label memoir. Show all posts

Sunday, November 3, 2019

Sunday, August 4, 2019

The Internet is My Religion by Jim Gilliam

Paperback, 194 pgs, Pub by NationBuilder (first published January 1st 2015), ISBN13: 9780996110402

You’re probably going to think a free memoir isn’t much—not interesting, not well-written, not worth bothering with. I picked it up at a conference not knowing it was a memoir. It sat around my house cluttering things until I decided to throw it out—but not until I glanced through it first.

Much later the same day it is all revolving in my head, leaving me feeling wonder, awe, thunderstruck surprise, joy, awe again. This is one helluva story, a creation story. a bildungsroman, an odyssey. And our hero—yes, emphatically, hero—emerges an adult, a moral adult caring about his fellow humans. His fellow humans care about him as well.

He is not bitter, or cynical, or any one of the things that lesser people may experience along the dark and scary road that can be our lives. His life surely trumps that of most of us, simply in terms of size: he is 6’9” and was down to 145 pounds at the height of his death-defying illness.

Since he tell us of his illness in the first pages, I am not giving away the story. No. That honor is still reserved for him because the bad things that happen are not really, ever, the story. It is what we did after that. And what Jim Gilliam did was to grab every bit of life he had left and use it.

By then he had discovered that God was not to be found in some cold pile of cathedral rocks somewhere or in the thundering denunciations of false prophets on TV. For him, God showed when we gathered together, in person or connected online, caring about and for one another, working towards a better, more perfect future. He calls that finding of connection a holy experience, and he is not wrong.

Gilliam is a technologist, and as such, one would expect his skills would not lie in writing. But this book, even if he had help, is beautifully done, full of moment, real insight, propulsion, and discovery. In a way, it is the tale of every man, though not every man has gotten there yet.

He will describe the moment he discovers falseness in the lessons taught him by his religious teachers, the moment the world begins to unravel around his family, the moment he discovers he must, no matter what, follow his own path to understanding.

What is so appealing about this journey is that Gilliam is guileless. He is not trying to teach us anything. He is explaining his journey, what he saw, and tells us what he thinks about what he saw. It is utterly fascinating because he has so much understanding of the events in his life.

Gilliam’s father and mother both were math majors and computer scientists of sorts in the computer field's early days. For business reasons his father lost an opportunity to develop one of the first software programs for personal computers at IBM and consequently turned to fundamentalist religion.

Gilliam grew up steeped in the language and an understanding of what computers could do, but was restricted from taking full advantage by the religiosity of his parents. He himself was very good at thinking like a scientist and took advanced classes while in high school so that he could enter college as a sophomore.

The hill separating him from his intellectual development became steeper just as he was finishing high school. I am not going to spoil the story arc. At no point did this 180-page small format paperback ever become weighted down with intent or causation. We just have the clean progression of one boy into man into—that word again—hero.

His understanding that there is something godly in human connection, in striving together for good, is exactly what people discover in moments of human happiness and fulfillment. While he rejected the morality in which he was raised, as I did, I wonder if somehow it wasn’t good preparation for recognizing morality when he saw it, finally.

Personally, I can’t think of a more absorbing, unputdownable story. Get it if you can. It is a wonderful, thought-provoking personal history.

Tweet

You’re probably going to think a free memoir isn’t much—not interesting, not well-written, not worth bothering with. I picked it up at a conference not knowing it was a memoir. It sat around my house cluttering things until I decided to throw it out—but not until I glanced through it first.

Much later the same day it is all revolving in my head, leaving me feeling wonder, awe, thunderstruck surprise, joy, awe again. This is one helluva story, a creation story. a bildungsroman, an odyssey. And our hero—yes, emphatically, hero—emerges an adult, a moral adult caring about his fellow humans. His fellow humans care about him as well.

He is not bitter, or cynical, or any one of the things that lesser people may experience along the dark and scary road that can be our lives. His life surely trumps that of most of us, simply in terms of size: he is 6’9” and was down to 145 pounds at the height of his death-defying illness.

Since he tell us of his illness in the first pages, I am not giving away the story. No. That honor is still reserved for him because the bad things that happen are not really, ever, the story. It is what we did after that. And what Jim Gilliam did was to grab every bit of life he had left and use it.

By then he had discovered that God was not to be found in some cold pile of cathedral rocks somewhere or in the thundering denunciations of false prophets on TV. For him, God showed when we gathered together, in person or connected online, caring about and for one another, working towards a better, more perfect future. He calls that finding of connection a holy experience, and he is not wrong.

Gilliam is a technologist, and as such, one would expect his skills would not lie in writing. But this book, even if he had help, is beautifully done, full of moment, real insight, propulsion, and discovery. In a way, it is the tale of every man, though not every man has gotten there yet.

He will describe the moment he discovers falseness in the lessons taught him by his religious teachers, the moment the world begins to unravel around his family, the moment he discovers he must, no matter what, follow his own path to understanding.

What is so appealing about this journey is that Gilliam is guileless. He is not trying to teach us anything. He is explaining his journey, what he saw, and tells us what he thinks about what he saw. It is utterly fascinating because he has so much understanding of the events in his life.

Gilliam’s father and mother both were math majors and computer scientists of sorts in the computer field's early days. For business reasons his father lost an opportunity to develop one of the first software programs for personal computers at IBM and consequently turned to fundamentalist religion.

Gilliam grew up steeped in the language and an understanding of what computers could do, but was restricted from taking full advantage by the religiosity of his parents. He himself was very good at thinking like a scientist and took advanced classes while in high school so that he could enter college as a sophomore.

The hill separating him from his intellectual development became steeper just as he was finishing high school. I am not going to spoil the story arc. At no point did this 180-page small format paperback ever become weighted down with intent or causation. We just have the clean progression of one boy into man into—that word again—hero.

His understanding that there is something godly in human connection, in striving together for good, is exactly what people discover in moments of human happiness and fulfillment. While he rejected the morality in which he was raised, as I did, I wonder if somehow it wasn’t good preparation for recognizing morality when he saw it, finally.

Personally, I can’t think of a more absorbing, unputdownable story. Get it if you can. It is a wonderful, thought-provoking personal history.

Tweet

Saturday, July 6, 2019

The Moment of Lift by Melinda Gates

Hardcover, 273 pgs, Pub April 23rd 2019 by Flatiron Books, ISBN13: 9781250313577

Melinda Gates has a famous name and job, but who knows what she actually does? Running a foundation with assets exceeding that of many countries must carry enormous stresses, particularly for people who understand that injecting cash into a problem may actually make the problem grow. What courage it must take just to try.

This had to have been a hard book to write, what with a crushing schedule, children, and weighty responsibilities, to say nothing of the disparate and discrete problems of women on different continents. I am not saying there aren’t similarities among women’s experiences the world over; I’m saying that, perhaps for the purposes of this book, on each continent Gates honed in on a different critical problem among women that she might be able to affect. In Africa, she showed us women responsible for field work and cultivation. In South Asia, we look at sex workers. In America, it was education. In every country the message was about empowerment and equality.

Gates sounds tentative and naïve to begin which may help her audience connect with her experience. But she has some insights sprinkled all the way along as we follow her progress from Catholic-school Texan to one of the few female programmers at a gung-ho win-at-any-cost Microsoft. Two early insights:

When speaking of her Catholicism and her support for birth control, that is, the notion that women must be able to control their own births, Gates says that religion and birth control should not be incompatible. She feels on strong moral ground and welcomes guidance from priests, nuns, and laypeople but “ultimately moral questions are personal questions. Majorities don’t matter on issues of conscience.” Drop mike. My hero. She gives me language to speak to critics who wish to roll back women’s right to choose. It’s not an easy decision but it is a woman’s decision. Otherwise, Christian critics, why did God give this ability to women alone?

Melinda shares some empowerment struggles of her own—in a company and in a household with Bill Gates. She was intimidated, but can you blame her? With support from Bill and from colleagues and friends, she managed to develop her innate ability to cooperate and thereby manage high-performing teams, both at the company and later at the foundation.

Later, Gates asks how does disrespect for women grow within a child suckling at his mother’s breast? Gates places the blame squarely on religion: “Disrespect for women grows when religions are dominated by men.” That is a brave stance, the articulation of which I am grateful. I also came to that conclusion, and it felt a lonely one. I wondered how my moral grounding felt so strong when I learned what I had in the Catholic tradition also. Perhaps our reactions are something along the lines of the questioning, probing Jesuitical tradition?

Women! stand up and show them how to both nurture and progress. Democrats and Republicans, we have way more in common as women than we have differences as political animals. And we have as much at stake. Those who are already empowered can make decisions on their own, so aren’t intimidated by women who may occasionally disagree. Isn't this how we learn? Those who seek empowerment can find it with other women, so join us. I definitely think there is room to work together to achieve something we haven’t yet managed here in the U.S. and need badly: coherence.

Gates’ last point is one close to the hearts of every mother, teacher, groundbreaker:

Gates has written a thought-provoking and generous book, sharing much of what she has been given.

Tweet

Melinda Gates has a famous name and job, but who knows what she actually does? Running a foundation with assets exceeding that of many countries must carry enormous stresses, particularly for people who understand that injecting cash into a problem may actually make the problem grow. What courage it must take just to try.

This had to have been a hard book to write, what with a crushing schedule, children, and weighty responsibilities, to say nothing of the disparate and discrete problems of women on different continents. I am not saying there aren’t similarities among women’s experiences the world over; I’m saying that, perhaps for the purposes of this book, on each continent Gates honed in on a different critical problem among women that she might be able to affect. In Africa, she showed us women responsible for field work and cultivation. In South Asia, we look at sex workers. In America, it was education. In every country the message was about empowerment and equality.

Gates sounds tentative and naïve to begin which may help her audience connect with her experience. But she has some insights sprinkled all the way along as we follow her progress from Catholic-school Texan to one of the few female programmers at a gung-ho win-at-any-cost Microsoft. Two early insights:

“I soon saw that if we are going to take our place as equals with men, it won’t come from winning our rights one by one or step by step; we’ll win our rights in waves as we become empowered…If you want to lift up humanity, empower women.”Gates wonders how she could have missed these two insights early in her foundation work, and I did, too, considering this was something Hillary Clinton hammered pretty hard during her years as First Lady and Secretary of State. Both Gates and Clinton had international reach and the massive resources to understand exactly where the latch was to unleash potential and creativity. Why Gates never mentions Clinton is a mystery, unless she is trying assiduously to avoid any political fallout. That can't be right, though, as Gates is pretty fearless weighing in on religious issues which have become political.

When speaking of her Catholicism and her support for birth control, that is, the notion that women must be able to control their own births, Gates says that religion and birth control should not be incompatible. She feels on strong moral ground and welcomes guidance from priests, nuns, and laypeople but “ultimately moral questions are personal questions. Majorities don’t matter on issues of conscience.” Drop mike. My hero. She gives me language to speak to critics who wish to roll back women’s right to choose. It’s not an easy decision but it is a woman’s decision. Otherwise, Christian critics, why did God give this ability to women alone?

Melinda shares some empowerment struggles of her own—in a company and in a household with Bill Gates. She was intimidated, but can you blame her? With support from Bill and from colleagues and friends, she managed to develop her innate ability to cooperate and thereby manage high-performing teams, both at the company and later at the foundation.

Later, Gates asks how does disrespect for women grow within a child suckling at his mother’s breast? Gates places the blame squarely on religion: “Disrespect for women grows when religions are dominated by men.” That is a brave stance, the articulation of which I am grateful. I also came to that conclusion, and it felt a lonely one. I wondered how my moral grounding felt so strong when I learned what I had in the Catholic tradition also. Perhaps our reactions are something along the lines of the questioning, probing Jesuitical tradition?

“Bias against women is perhaps humanity’s oldest prejudice, and not only are religions our oldest institutions, but they change more slowly and grudgingly than all the others—which means they hold on to their biases and blind spots longer.”When she is wrapping up, Gates shares something that will help all of us in this country as we struggle through the next period, trying to avoid the dangers of political and ideological attacks (from within!) on our constitution and on our future development and ability to face the existential dangers of climate change. She gives examples of women who have brought peace to warring factions in their country and says

”Many social movements are driven by the same combination—strong activism and the ability to take pain without passing it on. Anyone who can combine those two finds a voice with a moral force.”This, I submit, could be the very key to unlocking the potential of our future. Conservatives complain relentlessly about the yapping left. Essentially, I agree. We have to stop going to the least common denominator.

Women! stand up and show them how to both nurture and progress. Democrats and Republicans, we have way more in common as women than we have differences as political animals. And we have as much at stake. Those who are already empowered can make decisions on their own, so aren’t intimidated by women who may occasionally disagree. Isn't this how we learn? Those who seek empowerment can find it with other women, so join us. I definitely think there is room to work together to achieve something we haven’t yet managed here in the U.S. and need badly: coherence.

Gates’ last point is one close to the hearts of every mother, teacher, groundbreaker:

“Every society says its outsiders are the problem. But outsiders are not the problem; the urge to create outsiders is the problem. Overcoming that urge is our greatest challenge and our greatest promise."The Left is in agreement with the Right that every member of society must contribute something. No one wants to think they do not contribute. It is up to us to find ways for everyone to do so. And to those who insist they “got where they did by themselves,” well, go live by yourself. Praise your great wealth by looking in the mirror.

Gates has written a thought-provoking and generous book, sharing much of what she has been given.

Tweet

Labels:

Africa,

America,

Asia,

Flatiron Bks,

memoir,

nonfiction

Tuesday, July 2, 2019

The Making of a Justice by Justice John Paul Stevens

Hardcover, 560 pgs, Pub May 14th 2019 by Little, Brown and Company, ISBN13: 9780316489645

Justice John Paul Stevens appears to me to be one of those old-timey conservatives, the kind whose judgment I may not agree with but whose opinions I can respect. It’s been awhile since I’ve seen such clear thinking on the part of anyone who calls themselves Republican.

Stevens served on the Supreme Court thirty-four years, from 1975-2010. He did an awful lot of deciding in all that time; what I notice most is that these decisions, or at least the ones he discusses in detail, are ones that made a big difference in the life of ordinary Americans. We all knew the Supreme Court was important, but how quickly the perception of partisanship has begun to erode their power.

Stevens names time periods in the court for the newest member because that individual alters the balance of power. He discusses important decisions each new justice has authored that might be considered to define that justice’s body of work and places his own assents or dissents beside them.

One of the earliest discussions he wades into is the abortion debate. Stevens was seated two years after Roe v. Wade and says at the time the decision had no appearance of being controversial.

The 2003 case involving a challenge to the constitutionality of Pennsylvania’s 2002 congressional districting map, Vieth v. Jubelirer, is close to my heart. Hearing Stevens articulate why deciding partisan gerrymanders are not a heavy lift gives succor to like-minded in light of the devastation of a final refusal by SCOTUS to hear any more such cases.

Why is it any more difficult than deciding a racial gerrymander, he asks. Why can’t the Court stipulate every district boundary have a neutral justification? There are no lack of judicially manageable standards; there is a lack “judicial will to condemn even the most blatant violations of a state legislature’s fundamental duty to govern impartially.”

Stevens remained puzzled by his failure to convince his colleagues on the Court of his argument, an early echo of Justice Kagan’s distress this year that the blatant partisanship of the Court has broken out into the open and split the harmony with which they argued for so many years.

Stevens does not leave out decisions he wrote that were disliked by the country. Time never disguised the ugly truth that in Kelo v. The City of New London , a multinational pharmaceutical corporation looking around for a new development used the notion of eminent domain to take the homes of two long-time residents of New London, and then, within five years, closed up shop and left town. “…the Kelo majority opinion was rightly consistent with the Supreme Court’s precedent and the Constitution’s text and structure [but] Whether the decision represented sound policy is another matter.”

After the Citizen’s United decision with which he disagreed, Stevens tendered his resignation.

He revisits Alito’s record later, when he is wrapping up, to point out “especially striking” disagreements he had with him over interpretation of the Second Amendment. “Heller is unquestionably the most clearly incorrect decision that the Court announced during my tenure on the bench,” he says. [Alito] failed to appreciate the more limited relationship between gun ownership and liberty. Firearms, Stevens argues, “have a fundamentally ambivalent relationship to liberty.”

It probably wasn’t the Citizen’s United decision itself that brought the Stevens reign to an end; he may have had a small stroke after the pressures of that January decision and then playing a game a tennis. He was replaced by Elena Kagan, with whom he has professed to be delighted. Stevens didn’t so much change as a large portion of the country who once, and still do, call themselves Republicans moved to the right. Stevens never did and he was right where we needed him for thirty-four years.

Tweet

Justice John Paul Stevens appears to me to be one of those old-timey conservatives, the kind whose judgment I may not agree with but whose opinions I can respect. It’s been awhile since I’ve seen such clear thinking on the part of anyone who calls themselves Republican.

Stevens served on the Supreme Court thirty-four years, from 1975-2010. He did an awful lot of deciding in all that time; what I notice most is that these decisions, or at least the ones he discusses in detail, are ones that made a big difference in the life of ordinary Americans. We all knew the Supreme Court was important, but how quickly the perception of partisanship has begun to erode their power.

Stevens names time periods in the court for the newest member because that individual alters the balance of power. He discusses important decisions each new justice has authored that might be considered to define that justice’s body of work and places his own assents or dissents beside them.

One of the earliest discussions he wades into is the abortion debate. Stevens was seated two years after Roe v. Wade and says at the time the decision had no appearance of being controversial.

Criticism of Roe became more widespread perhaps in part because opponents repeatedly make the incorrect argument that only a “right to privacy,” unmentioned in the Constitution, supported the holding. Correctly basing a woman’s right to have an abortion in "liberty" rather than “privacy" should undercut that criticism.Just so.

The 2003 case involving a challenge to the constitutionality of Pennsylvania’s 2002 congressional districting map, Vieth v. Jubelirer, is close to my heart. Hearing Stevens articulate why deciding partisan gerrymanders are not a heavy lift gives succor to like-minded in light of the devastation of a final refusal by SCOTUS to hear any more such cases.

Why is it any more difficult than deciding a racial gerrymander, he asks. Why can’t the Court stipulate every district boundary have a neutral justification? There are no lack of judicially manageable standards; there is a lack “judicial will to condemn even the most blatant violations of a state legislature’s fundamental duty to govern impartially.”

Stevens remained puzzled by his failure to convince his colleagues on the Court of his argument, an early echo of Justice Kagan’s distress this year that the blatant partisanship of the Court has broken out into the open and split the harmony with which they argued for so many years.

Stevens does not leave out decisions he wrote that were disliked by the country. Time never disguised the ugly truth that in Kelo v. The City of New London , a multinational pharmaceutical corporation looking around for a new development used the notion of eminent domain to take the homes of two long-time residents of New London, and then, within five years, closed up shop and left town. “…the Kelo majority opinion was rightly consistent with the Supreme Court’s precedent and the Constitution’s text and structure [but] Whether the decision represented sound policy is another matter.”

After the Citizen’s United decision with which he disagreed, Stevens tendered his resignation.

“…it is perfectly clear that if the identity of a speaker cannot provide the basis for regulating his (or its) speech, the majority’s rationale in Citizen’s United would protect not only the foreign shareholders of corporate donors to political campaigns but also foreign corporate donors themselves.”By hardly ever mentioning fellow Justice Sam Alito Stevens shows his animus. After this decision, Stevens describes Alito sitting in the audience during Obama’s State of the Union. When Obama mentioned that the decision allows foreign corporations to have a say in American elections, Stevens writes Alito “incorrectly” mouthed the words: “Not true.”

He revisits Alito’s record later, when he is wrapping up, to point out “especially striking” disagreements he had with him over interpretation of the Second Amendment. “Heller is unquestionably the most clearly incorrect decision that the Court announced during my tenure on the bench,” he says. [Alito] failed to appreciate the more limited relationship between gun ownership and liberty. Firearms, Stevens argues, “have a fundamentally ambivalent relationship to liberty.”

It probably wasn’t the Citizen’s United decision itself that brought the Stevens reign to an end; he may have had a small stroke after the pressures of that January decision and then playing a game a tennis. He was replaced by Elena Kagan, with whom he has professed to be delighted. Stevens didn’t so much change as a large portion of the country who once, and still do, call themselves Republicans moved to the right. Stevens never did and he was right where we needed him for thirty-four years.

Tweet

Labels:

biography,

government,

legal,

Little Brown,

memoir,

nonfiction,

politics

Wednesday, June 12, 2019

Lead from the Outside by Stacey Abrams

Paperback, 256 pgs, Pub March 26th 2019 by Picador (first published April 24th 2018), ISBN13: 9781250214805

Stacey Abrams learned to not always kick directly at her goal. Watching her stand back and assess a situation can be a fearsome thing. You know she is going to do something oh-so-effective and she is going to use her team to get there, those who mentored her and those she mentored herself. I just love that teamwork.

This memoir is unlike any other presidential-hopeful memoir out there. Abrams has not declared herself for the 2020 race, but running for president is on her to-do list. I read the library edition of her book quickly and wondered why she’d write it this way; she’s a writer and this is written in a workbook self-help style. But something she’d said about ambition was so clarifying and electrifying that I ended up buying the book to study what she was doing.

Now I know why Abrams wrote her book like this. After all, she could have written whatever kind of book she wanted. Her ambition is to have readers feel strong and capable enough to do whatever they put their minds to, whether it is to aid someone in office or be that person in office. She learned a lot on her path to this place and she doesn’t necessarily want to get to the top of the mountain without her cohort. Her ambition is not an office, it is a result.

What Abrams relates about her failures is most instructive. After all, none of us achieve all we set our minds to, at least on the first try. But Abrams shows that one has to be relentlessly honest with oneself about one’s advantages and deficiencies, even asking others in case one’s own interpretations are skewed by fear or previous failure. By writing her book this way, Abrams is unapologetic about some areas she could have handled better, personal finances for instance, that could have been used as a weapon against her. She explains her situation at the time and recommends better pathways for those who follow.

A former member of the Georgia State Legislature, Abrams found herself a different breed of politician than most who had achieved that rank. She was less attuned to social sway than she was to marshaling her intellect to overcome roadblocks to effective legislation. This undoubtedly had some genesis in the reactions she’d gotten her entire life as a black woman. She wasn’t going to wait for folks to accept her; she planned to take her earned seat at the table but she was going to be prepared.

She found that she needed both skills to succeed in business and in politics. She needed the support of a base and she needed an understanding of what would move the ball forward. And she learned what real power means.

If defeat is inevitable, reevaluate. Abrams suggests that one may need to change the rules of engagement so that instead of a ‘win’ one may be happy to ‘stay alive’ to fight another day.

The last fifty pages of the book put words to things we may know but haven’t articulated before. Abrams acknowledges that beliefs are anchors which help to direct us in decision-making but should never be used to block critical thinking, reasonable compromise, and thoughtful engagement.

It is difficult to believe there is anyone out there who doesn’t admire Stacey Abrams’ guts and perseverance. Her friends stood by her in times of stress because Abrams made efforts to acknowledge her weaknesses while not allowing them to break down her spirit. She built every pillar of the leadership role she talks about and can stand before us, challenging us to do the same. She is a powerhouse.

Tweet

Stacey Abrams learned to not always kick directly at her goal. Watching her stand back and assess a situation can be a fearsome thing. You know she is going to do something oh-so-effective and she is going to use her team to get there, those who mentored her and those she mentored herself. I just love that teamwork.

This memoir is unlike any other presidential-hopeful memoir out there. Abrams has not declared herself for the 2020 race, but running for president is on her to-do list. I read the library edition of her book quickly and wondered why she’d write it this way; she’s a writer and this is written in a workbook self-help style. But something she’d said about ambition was so clarifying and electrifying that I ended up buying the book to study what she was doing.

“Ambition should be an animation of soul…a disquiet that requires you to take action…Ambition means being proactive…If you can walk away [from your ambition] for days, weeks, or years at a time, it is not an ambition—it’s a wish.”Ambition is not something you can be passive about. You feel you must act on it or you will regret it all your days. Ambition should not a job title but something that helps you to answer “why”.

Now I know why Abrams wrote her book like this. After all, she could have written whatever kind of book she wanted. Her ambition is to have readers feel strong and capable enough to do whatever they put their minds to, whether it is to aid someone in office or be that person in office. She learned a lot on her path to this place and she doesn’t necessarily want to get to the top of the mountain without her cohort. Her ambition is not an office, it is a result.

What Abrams relates about her failures is most instructive. After all, none of us achieve all we set our minds to, at least on the first try. But Abrams shows that one has to be relentlessly honest with oneself about one’s advantages and deficiencies, even asking others in case one’s own interpretations are skewed by fear or previous failure. By writing her book this way, Abrams is unapologetic about some areas she could have handled better, personal finances for instance, that could have been used as a weapon against her. She explains her situation at the time and recommends better pathways for those who follow.

A former member of the Georgia State Legislature, Abrams found herself a different breed of politician than most who had achieved that rank. She was less attuned to social sway than she was to marshaling her intellect to overcome roadblocks to effective legislation. This undoubtedly had some genesis in the reactions she’d gotten her entire life as a black woman. She wasn’t going to wait for folks to accept her; she planned to take her earned seat at the table but she was going to be prepared.

She found that she needed both skills to succeed in business and in politics. She needed the support of a base and she needed an understanding of what would move the ball forward. And she learned what real power means.

“Access to real power also acknowledges that sometimes we need to collaborate rather than compete. We have to work with our least favorite colleague or with folks whose ideologies differ greatly from our own…But working together for a common end, if not for the same reason, means that more can be accomplished.”Abrams discusses strategies and tactics for acquiring and wielding power and reminds us that “sometimes winning takes longer than we hope” and leaders facing long odds on worthy goals best be prepared for the “slow-burn” where victory doesn’t arrive quickly. But every small victory or single act of defiance can inspire someone else to take action.

If defeat is inevitable, reevaluate. Abrams suggests that one may need to change the rules of engagement so that instead of a ‘win’ one may be happy to ‘stay alive’ to fight another day.

The last fifty pages of the book put words to things we may know but haven’t articulated before. Abrams acknowledges that beliefs are anchors which help to direct us in decision-making but should never be used to block critical thinking, reasonable compromise, and thoughtful engagement.

“Collaboration and compromise are necessary tools in gaining and holding power.”The GOP also believes this, but I think they use the notion within their coalition: they use discipline to keep their team in order and members may need to compromise their values to stay in the power group. Democrats must hold onto the notion of compromise within and without their coalition to succeed, while never compromising values.

It is difficult to believe there is anyone out there who doesn’t admire Stacey Abrams’ guts and perseverance. Her friends stood by her in times of stress because Abrams made efforts to acknowledge her weaknesses while not allowing them to break down her spirit. She built every pillar of the leadership role she talks about and can stand before us, challenging us to do the same. She is a powerhouse.

Tweet

Labels:

America,

government,

HH,

memoir,

nonfiction,

Picador,

politics,

race

Thursday, May 9, 2019

On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong

Hardcover, 256 pgs, Expected publication: June 4th 2019 by Penguin Press, ISBN13: 9780525562023

This work is called a novel but it is a ball of flame tossed into a dark night, blinding, brilliant, searing. Who knows if it is poetry or novel or memoir; the language fills the mouth and is saturated with truth. We recognize it. We’ve tasted it. We are pained by it. It still hurts.

Something here is reminiscent of the epic poetry of Homer. Life's brutality, man’s frailty, the odyssey, the clash of civilizations, the incomparable language undeniably capturing human experience, these things make Vuong someone who heightens our awareness, deepens our experience, shocks us into acknowledgement of our shared experiences. What have we in common with a Greek of ancient times singing of a war and the personal trials of man? What have we in common with a gay immigrant boy writing of war and the personal trials of man?

The story is clear enough but fragmentary. In a Nov 2017 LitHub interview, Vuong tells us

The language Vuong brings is exquisite and extraordinary: “The fluorescent hums steady above them, as if the scene is a dream the light is having.” “…the thing about beauty is that it’s only beautiful outside of itself.” “The carpet under his bare feet is shiny as spilled oil from years of wear.” “…repeating piles of rotted firewood, the oily mounds gone mushy…” “He had a thick face and pomaded hair, even at this hour, like Elvis on on his last day on earth.”

Vuong repeats motifs to tie the experiences of one person to the rest of his life, to tie one person’s experiences to those of others: “I’m at war.” “We cracked up. We cracked open.” “…you never see yourself if you’re the sun. You don’t even know where you are in the sky.” “…my cheek bone stinging from the first blow.” “I was yellow.”

A teen, immigrated to the U.S. from Vietnam with his mother, grandmother, and aunt finds himself fleeing his “shitty high school to spend [his] days in New York lost in library stacks,” from whence he, first in this family to go to college, squanders his opportunity on an English degree.

The teen discovers his gayness and does not flee it, though his white lover agonizes and denies all his life. We watch that boy fall, wither, die under the scourge of fentanyl and opioid addiction and Vuong places the scourge in the wider context of an awry world.

Despite (or perhaps because of) the fragmented, shattered nature of the tale, there is a real momentum to this novel, Vuong telling us things not articulated in this way before: a familiar war from a new angle, the friction burn of the immigrant experience, the roughness of gay sex, the madness of living untethered in the world. The language is so precise, so surprising, so wide-awake and fresh, that we read to see.

Last year, in September of 2018, I reviewed Vuong’s first book of poetry, Night Sky with Exit Wounds. The poems had many of the same tendencies toward epic poetry—they were big, and meaningful. Below I have attached a short video of Vuong reading from that collection to give you some idea of his power.

Among his honors, he is a recipient of the 2014 Ruth Lilly/Sargent Rosenberg fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, a 2016 Whiting Award, and the 2017 T.S. Eliot Prize. He is an Assistant Professor in the MFA Program for Writers at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. He is thirty years old.

Tweet

This work is called a novel but it is a ball of flame tossed into a dark night, blinding, brilliant, searing. Who knows if it is poetry or novel or memoir; the language fills the mouth and is saturated with truth. We recognize it. We’ve tasted it. We are pained by it. It still hurts.

Something here is reminiscent of the epic poetry of Homer. Life's brutality, man’s frailty, the odyssey, the clash of civilizations, the incomparable language undeniably capturing human experience, these things make Vuong someone who heightens our awareness, deepens our experience, shocks us into acknowledgement of our shared experiences. What have we in common with a Greek of ancient times singing of a war and the personal trials of man? What have we in common with a gay immigrant boy writing of war and the personal trials of man?

The story is clear enough but fragmentary. In a Nov 2017 LitHub interview, Vuong tells us

”I’m writing a novel composed of woven inter-genre fragments. To me, a book made entirely out of unbridged fractures feels most faithful to the physical and psychological displacement I experience as a human being. I’m interested in a novel that consciously rejects the notion that something has to be whole in order to tell a complete story. I also want to interrogate the arbitrary measurements of a “successful” literary work, particularly as it relates to canonical Western values. For example, we traditionally privilege congruency and balance in fiction, we want our themes linked, our conflicts “resolved,” and our plots “ironed out.” But when one arrives at the page through colonized, plundered, and erased histories and diasporas, to write a smooth and cohesive novel is to ultimately write a lie. In a way, I’m curious about a work that rejects its patriarchal predecessors as a way of accepting its fissured self. I think, perennially, of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée. This resistance to dominant convention is not only the isolated concern of marginalized writers—but all writers—and perhaps especially white writers, who can gain so much by questioning how the ways we value art can replicate the very oppressive legacies we strive to end.”The novel he speaks of is this one. I did not understand that paragraph when I first read it as well as I do now. I am more aware, too, having looked closely for the Western world’s acknowledged historical tendency to erase or ignore pieces of experience not congruent with their own worldview.

The language Vuong brings is exquisite and extraordinary: “The fluorescent hums steady above them, as if the scene is a dream the light is having.” “…the thing about beauty is that it’s only beautiful outside of itself.” “The carpet under his bare feet is shiny as spilled oil from years of wear.” “…repeating piles of rotted firewood, the oily mounds gone mushy…” “He had a thick face and pomaded hair, even at this hour, like Elvis on on his last day on earth.”

Vuong repeats motifs to tie the experiences of one person to the rest of his life, to tie one person’s experiences to those of others: “I’m at war.” “We cracked up. We cracked open.” “…you never see yourself if you’re the sun. You don’t even know where you are in the sky.” “…my cheek bone stinging from the first blow.” “I was yellow.”

A teen, immigrated to the U.S. from Vietnam with his mother, grandmother, and aunt finds himself fleeing his “shitty high school to spend [his] days in New York lost in library stacks,” from whence he, first in this family to go to college, squanders his opportunity on an English degree.

The teen discovers his gayness and does not flee it, though his white lover agonizes and denies all his life. We watch that boy fall, wither, die under the scourge of fentanyl and opioid addiction and Vuong places the scourge in the wider context of an awry world.

Despite (or perhaps because of) the fragmented, shattered nature of the tale, there is a real momentum to this novel, Vuong telling us things not articulated in this way before: a familiar war from a new angle, the friction burn of the immigrant experience, the roughness of gay sex, the madness of living untethered in the world. The language is so precise, so surprising, so wide-awake and fresh, that we read to see.

Last year, in September of 2018, I reviewed Vuong’s first book of poetry, Night Sky with Exit Wounds. The poems had many of the same tendencies toward epic poetry—they were big, and meaningful. Below I have attached a short video of Vuong reading from that collection to give you some idea of his power.

Among his honors, he is a recipient of the 2014 Ruth Lilly/Sargent Rosenberg fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, a 2016 Whiting Award, and the 2017 T.S. Eliot Prize. He is an Assistant Professor in the MFA Program for Writers at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. He is thirty years old.

Tweet

Sunday, May 5, 2019

Shortest Way Home by Pete Buttigieg

Hardcover, 352 pgs, Pub February 12th 2019 by Liveright, ISBN13: 9781631494369

Since beginning Buttigieg's book, I have travelled across the country and spoken with lots of folks outside of my usual cabal. Nearly everyone I spoke with had heard of Buttigieg, current Mayor of South Bend, Indiana, running for President as a Democratic candidate. Only one of the people I spoke with mentioned his homosexuality as a reason for his possible failure to connect, and the same person was also skeptical about his age.

Buttigieg himself would remind voters that his age has been the thing that conversely has energized people, particularly older voters, who recognize that their generation left his generation with a big problem when it comes to climate change. Older people who have no stake in what will come are unlikely to move the needle as far and as fast as it needs to move. Time to step aside and hope for fresh ideas. At least that is what Buttigieg is peddling.

When I listen to him talk, I agree. I just want all the old men and women who have left both parties in a shambles with attempts to hold onto power (What power do they exhibit, may I ask? It’s positively derisive.) to leave the stage asap.

This book is easy enough to read, though does not rank with Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father which broke the mold on literary presidential memoirs. Truthfully, I picked up the book in the midst of an infatuation with Buttigieg’s calm sense and blunt assessments, and before I finished, I felt the bloom had left the rose. I still admire him and definitely consider him a frontrunner but I am not infatuated anymore. This is a good thing. I go into my support of his candidacy with a clear head.

Buttigieg is genuinely talented in languages, and it makes one wish we learned what he did from his linguist mother. One of my favorite of his stories is when he told Navy recruiters that he’d studied Arabic in hopes of landing an intelligence job at a desk somewhere and they wrote down that he’d studied “aerobics.” That is classic SNAFU.

Buttigieg describes the feeling at rallies for presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. The two rallies had the ambiance of a party, but while Bernie’s parties seem joyous and goofy—Bernie with the finch, Bernie riding a unicorn, buttons featuring glasses and hair—Donald Trump’s parties have a edge, like a party where “you’re not sure if a fight will break out.” This is good storytelling. We know exactly what he is saying and can feel the roil.

What kills me about Buttigieg is that he is so quiet about some of his biggest accomplishments, e.g., he applied for a Rhodes scholarship and got it, he decided to run for president and he is a frontrunner. He doesn't thrash about explaining his calculations: a nobody mayor of a small city calmly and quietly declares an exploratory committee and begins criss-crossing the country before anyone else has even thought to get into the race and captures a lot of press because of his youth and his self-possession.

He could see the Democratic party had lost its way, punctuated by the loss in 2016, to say nothing of the turmoil in what used to be a Republican party. He could see that sitting back and watching ‘the clash of the white hairs’ was not going to advance us because these folks appear bewildered by where we have landed. He thought he could be useful, pointing out the obvious and taking steps to address some of our most urgent issues. Gosh darn it if he isn’t.

One of the more startling and interesting things Buttigieg said about government is that

Way back in the 1970’s and 80’s Lee Atwater, a Republican strategist, figured this out and moved to capturing the heartland. That strategy has brought us gerrymandering and court-packing and other state-level indications of one-party dominance. But local governments are finding that counties walking in lock-step to the state does not always work for their particular conditions. There is great inequality as a result of GOP leadership at the state level. What is government about anyway?

A Koch Brothers-funded think tank called the American Legislative Exchange Council is pointed to as generating model legislation for adoption in state legislatures and finds sympathetic state actors to carry the bills.

Buttigieg makes the point that many folks got involved in local and county government as a matter of course in their lives, as one aspect of community participation, and they chose the most organized party to help them on their way. That would be the Republican party. They are pretty inculcated with the party line after a few years, but they may not agree with everything the party posts. That is why Indianans could vote for both Mike Pence and Pete Buttigieg. Voters really can read, think, make up their own minds.

We have to be in it to win it. I am more and more reluctant to declare myself Democrat after seeing some of the shenanigans local, state, and national leaders get up to. But I’ll be damned if I’ll sit by and watch the plotters and weavers poison the well. If ever there was a time to stand up and participate with your voices, now is that time. Choose your issues, decide at which level you can intervene, look to see where you might have some degree of influence, and get engaged. No more cheering from the sidelines.

Tweet

Since beginning Buttigieg's book, I have travelled across the country and spoken with lots of folks outside of my usual cabal. Nearly everyone I spoke with had heard of Buttigieg, current Mayor of South Bend, Indiana, running for President as a Democratic candidate. Only one of the people I spoke with mentioned his homosexuality as a reason for his possible failure to connect, and the same person was also skeptical about his age.

Buttigieg himself would remind voters that his age has been the thing that conversely has energized people, particularly older voters, who recognize that their generation left his generation with a big problem when it comes to climate change. Older people who have no stake in what will come are unlikely to move the needle as far and as fast as it needs to move. Time to step aside and hope for fresh ideas. At least that is what Buttigieg is peddling.

When I listen to him talk, I agree. I just want all the old men and women who have left both parties in a shambles with attempts to hold onto power (What power do they exhibit, may I ask? It’s positively derisive.) to leave the stage asap.

This book is easy enough to read, though does not rank with Barack Obama’s Dreams from My Father which broke the mold on literary presidential memoirs. Truthfully, I picked up the book in the midst of an infatuation with Buttigieg’s calm sense and blunt assessments, and before I finished, I felt the bloom had left the rose. I still admire him and definitely consider him a frontrunner but I am not infatuated anymore. This is a good thing. I go into my support of his candidacy with a clear head.

Buttigieg is genuinely talented in languages, and it makes one wish we learned what he did from his linguist mother. One of my favorite of his stories is when he told Navy recruiters that he’d studied Arabic in hopes of landing an intelligence job at a desk somewhere and they wrote down that he’d studied “aerobics.” That is classic SNAFU.

Buttigieg describes the feeling at rallies for presidential candidates Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. The two rallies had the ambiance of a party, but while Bernie’s parties seem joyous and goofy—Bernie with the finch, Bernie riding a unicorn, buttons featuring glasses and hair—Donald Trump’s parties have a edge, like a party where “you’re not sure if a fight will break out.” This is good storytelling. We know exactly what he is saying and can feel the roil.

What kills me about Buttigieg is that he is so quiet about some of his biggest accomplishments, e.g., he applied for a Rhodes scholarship and got it, he decided to run for president and he is a frontrunner. He doesn't thrash about explaining his calculations: a nobody mayor of a small city calmly and quietly declares an exploratory committee and begins criss-crossing the country before anyone else has even thought to get into the race and captures a lot of press because of his youth and his self-possession.

He could see the Democratic party had lost its way, punctuated by the loss in 2016, to say nothing of the turmoil in what used to be a Republican party. He could see that sitting back and watching ‘the clash of the white hairs’ was not going to advance us because these folks appear bewildered by where we have landed. He thought he could be useful, pointing out the obvious and taking steps to address some of our most urgent issues. Gosh darn it if he isn’t.

One of the more startling and interesting things Buttigieg said about government is that

“some of the most important policy dynamics of our time have to do with the relationships, and the tension, between state and local government.”I pulled that quote out for you to see because I think this is something national pundits and talking heads miss completely.

Way back in the 1970’s and 80’s Lee Atwater, a Republican strategist, figured this out and moved to capturing the heartland. That strategy has brought us gerrymandering and court-packing and other state-level indications of one-party dominance. But local governments are finding that counties walking in lock-step to the state does not always work for their particular conditions. There is great inequality as a result of GOP leadership at the state level. What is government about anyway?

A Koch Brothers-funded think tank called the American Legislative Exchange Council is pointed to as generating model legislation for adoption in state legislatures and finds sympathetic state actors to carry the bills.

“Legislation is often nearly identical from state to state—so much so that journalists sometimes find copy-paste errors where the wrong state is mentioned in the text of a bill. Tellingly, by 2014, ALEC had decided to expand its model beyond the state level—not by going federal, but instead targeting local policy through a new offshoot called the American City County Exchange.”Democrats must be willing to compete in red zones—many times it is only because they are not competing that they have less support.

Buttigieg makes the point that many folks got involved in local and county government as a matter of course in their lives, as one aspect of community participation, and they chose the most organized party to help them on their way. That would be the Republican party. They are pretty inculcated with the party line after a few years, but they may not agree with everything the party posts. That is why Indianans could vote for both Mike Pence and Pete Buttigieg. Voters really can read, think, make up their own minds.

We have to be in it to win it. I am more and more reluctant to declare myself Democrat after seeing some of the shenanigans local, state, and national leaders get up to. But I’ll be damned if I’ll sit by and watch the plotters and weavers poison the well. If ever there was a time to stand up and participate with your voices, now is that time. Choose your issues, decide at which level you can intervene, look to see where you might have some degree of influence, and get engaged. No more cheering from the sidelines.

Tweet

Monday, March 25, 2019

Let Her Fly: A Father's Journey by Ziauddin Yousafzai with Louise Carpenter

Hardcover, 170 pgs, Pub Nov 13th 2018 by Little, Brown and Company, ISBN13: 9780316450508

This book caught my eye across a crowded library. What must it have been like to experience the phenomenon that is Malala Yousafzai and what were the earliest manifestations of her exceptionality?

Ziauddin Yousafzai was unusual himself. He and his brothers all had severe stammers growing up, but not his sisters. Of course the boys bore the brunt of family expectations. He took on a challenge to become an outstanding public speaker, delivering a speech his father helped him to craft. When he won first place in the competition, he continued his effort to overcome his speech impediment through public speaking.

Ziauddin was a feminist before the word was popular in Pakistan and when he married and moved with his wife, Toor Pekai, to Swat, his wife took advantage of his encouragement to embrace small freedoms during their life there. Their first daughter would be a much more enthusiastic reformer, willing to cover her head but not her face. Malala often sat with her father’s friends and answered questions of opinion he would put to her. She became a skilled public speaker through his influence, and she won many public speaking awards on her favorite topic: the rights and education of girls.

Malala was exceptionally bright and curious from an early age and attracted the attention of visitors to the Yousafzai household. She also broke down the resistance to change by her conservative grandfather. She attended a school run by her father and excelled, far more than her brothers who were ordinary in schoolwork. The Yousafzai school encourage all local girls to attend, and had a large number.

The campaign in which Yousafzai and his daughter Malala engaged to save girls education had been going against the Taliban’s edicts for about five years when the attack on her occurred. She was fifteen.

There is detail about Malala being flown by helicopter from one hospital to another, to gradually larger ones with more surgical expertise, until she finally is set down in Birmingham, England, where they take off any blood pressuring her brain, happily discovering there was no impingement on her cognitive function. She began a long series of reconstructive surgeries to lessen the impact of the nerve damage to her face.

Living in England turned the family dynamic 180 degrees. Malala had been a strong presence and leader in the family. While she was incapacitated, her younger brothers took on critical roles interfacing with British culture. The parents admit they resisted the power inversion at first, feeling out of their element, but gradually they were grateful for the boys' facility in the new environment and relied on them. The family grew closer in crisis because everyone came to recognize and accept their strengths and weaknesses.

Malala’s recovery was undoubtedly due to support from her family, but also grew from her own inner strength. The damage inflicted on her gave her more opportunity to develop an extraordinary resilience, and the long recovery gave her the opportunity to concentrate on her studies.

Tweet

This book caught my eye across a crowded library. What must it have been like to experience the phenomenon that is Malala Yousafzai and what were the earliest manifestations of her exceptionality?

Ziauddin Yousafzai was unusual himself. He and his brothers all had severe stammers growing up, but not his sisters. Of course the boys bore the brunt of family expectations. He took on a challenge to become an outstanding public speaker, delivering a speech his father helped him to craft. When he won first place in the competition, he continued his effort to overcome his speech impediment through public speaking.

Ziauddin was a feminist before the word was popular in Pakistan and when he married and moved with his wife, Toor Pekai, to Swat, his wife took advantage of his encouragement to embrace small freedoms during their life there. Their first daughter would be a much more enthusiastic reformer, willing to cover her head but not her face. Malala often sat with her father’s friends and answered questions of opinion he would put to her. She became a skilled public speaker through his influence, and she won many public speaking awards on her favorite topic: the rights and education of girls.

Malala was exceptionally bright and curious from an early age and attracted the attention of visitors to the Yousafzai household. She also broke down the resistance to change by her conservative grandfather. She attended a school run by her father and excelled, far more than her brothers who were ordinary in schoolwork. The Yousafzai school encourage all local girls to attend, and had a large number.

The campaign in which Yousafzai and his daughter Malala engaged to save girls education had been going against the Taliban’s edicts for about five years when the attack on her occurred. She was fifteen.

There is detail about Malala being flown by helicopter from one hospital to another, to gradually larger ones with more surgical expertise, until she finally is set down in Birmingham, England, where they take off any blood pressuring her brain, happily discovering there was no impingement on her cognitive function. She began a long series of reconstructive surgeries to lessen the impact of the nerve damage to her face.

Living in England turned the family dynamic 180 degrees. Malala had been a strong presence and leader in the family. While she was incapacitated, her younger brothers took on critical roles interfacing with British culture. The parents admit they resisted the power inversion at first, feeling out of their element, but gradually they were grateful for the boys' facility in the new environment and relied on them. The family grew closer in crisis because everyone came to recognize and accept their strengths and weaknesses.

Malala’s recovery was undoubtedly due to support from her family, but also grew from her own inner strength. The damage inflicted on her gave her more opportunity to develop an extraordinary resilience, and the long recovery gave her the opportunity to concentrate on her studies.

Whenever anybody has asked me how Malala became who she is, I have often used the response "Ask me not what I did but what I did not do. I did not clip her wings."The Yousafzai family members each have a quality of gratefulness that is so attractive, allowing each one to occasionally take a supporting role to another's exceptionalism. That less-lauded role is equally difficult to perform. The entire family deserves credit for surviving with such strength of character, but that specialness may stem from the leadership of Ziauddin Yousafzai, which is why this book is about him.

Tweet

Friday, March 22, 2019

An Unlikely Journey by Julián Castro

Hardcover, 288 pgs, Pub Oct 16th 2018 by Little, Brown and Company, ISBN13: 9780316252164

Memoirs are de rigueur for anyone aspiring to the presidency. And so they should be, to introduce themselves and to give us an idea from where their sense of duty emanates. Nonetheless, it is disorienting to read the memoir of someone in their forties running for president who never mentions travel abroad.

At least half this book is composed of Julián’s life before he was twenty. For those who argue that “youthful indiscretions don’t matter,” here is someone who clearly thinks one’s sense of self and others grows up with you.

While I might go along with that notion of human development, it is the time after age twenty when we have to make decisions that really show who we are. After graduating from Stanford University and Harvard Law, Castro returned to his home city of San Antonio, took a job with a law firm and promptly ran for San Antonio City Council in his home district and won.

Right out of the gate was a big conflict of interest. Castro’s law firm represented a developer who wanted to build a golf course over the city’s aquifer and get a tax break to do it. Castro quit his paying job with the law firm, ended up voting no on the proposal with the backing of 56% of San Antonio residents.

The initial project failed--not because of his vote--but another came right behind it, this time for two golf courses, but with stronger environmental protections and no tax breaks. Castro voted for the project the second time. He uses the example of this project to show the importance of local government work, but also what people can do when they have principled objections and work together.

The experience fueled Castro’s interest in higher office. He lost at his first attempt to run for mayor of San Antonio, and it looks like it was his first big public failure. He felt humiliated. But like everyone who eventually succeeds, he had to pick himself up and do it again, which he did, winning in 2009. After that, he went back and forth to Washington, as head of HUD under Obama, and then mentioned as vice-presidential pick during the run up to the 2016 election.

It takes a special personality to want the blood sport that is politics. Castro learned the power of the people from his mother, who was known for her organizing work. He has a twin brother who absorbed the same lessons and worked alongside him to set up and win elections while they were in college and after. But what makes one reach for the highest office?

We all have to find the answer to that one, and while I am not impressed with those who want to see their names in lights—or gold letters eight feet high—there are people who are at least as capable as the rest of us but who want the limelight. I’m willing to give it to them if it makes sense for the direction we need to move.

Julián Castro is not ready, to my mind, to run for the presidency. I do not get the reassurance he even knows what it is. I don't mind some learning on the job, but look at what Teresa May just went through. There is a largeness to the job that will always exceed our best attempts to put our arms around it. Do I think he would be worthy some day? Maybe.

What we are doing now in our presidential slates--going as old as we can and as young as we can--is unappealing to me. Precociousness is a real thing, and I don't want to stand in the way of talent. To me, Castro for President is premature, but I have to admit the world belongs to the young now, who are going to have to find a way to live in it.

Tweet

Memoirs are de rigueur for anyone aspiring to the presidency. And so they should be, to introduce themselves and to give us an idea from where their sense of duty emanates. Nonetheless, it is disorienting to read the memoir of someone in their forties running for president who never mentions travel abroad.

At least half this book is composed of Julián’s life before he was twenty. For those who argue that “youthful indiscretions don’t matter,” here is someone who clearly thinks one’s sense of self and others grows up with you.

While I might go along with that notion of human development, it is the time after age twenty when we have to make decisions that really show who we are. After graduating from Stanford University and Harvard Law, Castro returned to his home city of San Antonio, took a job with a law firm and promptly ran for San Antonio City Council in his home district and won.

Right out of the gate was a big conflict of interest. Castro’s law firm represented a developer who wanted to build a golf course over the city’s aquifer and get a tax break to do it. Castro quit his paying job with the law firm, ended up voting no on the proposal with the backing of 56% of San Antonio residents.

The initial project failed--not because of his vote--but another came right behind it, this time for two golf courses, but with stronger environmental protections and no tax breaks. Castro voted for the project the second time. He uses the example of this project to show the importance of local government work, but also what people can do when they have principled objections and work together.

The experience fueled Castro’s interest in higher office. He lost at his first attempt to run for mayor of San Antonio, and it looks like it was his first big public failure. He felt humiliated. But like everyone who eventually succeeds, he had to pick himself up and do it again, which he did, winning in 2009. After that, he went back and forth to Washington, as head of HUD under Obama, and then mentioned as vice-presidential pick during the run up to the 2016 election.

It takes a special personality to want the blood sport that is politics. Castro learned the power of the people from his mother, who was known for her organizing work. He has a twin brother who absorbed the same lessons and worked alongside him to set up and win elections while they were in college and after. But what makes one reach for the highest office?

We all have to find the answer to that one, and while I am not impressed with those who want to see their names in lights—or gold letters eight feet high—there are people who are at least as capable as the rest of us but who want the limelight. I’m willing to give it to them if it makes sense for the direction we need to move.

Julián Castro is not ready, to my mind, to run for the presidency. I do not get the reassurance he even knows what it is. I don't mind some learning on the job, but look at what Teresa May just went through. There is a largeness to the job that will always exceed our best attempts to put our arms around it. Do I think he would be worthy some day? Maybe.

What we are doing now in our presidential slates--going as old as we can and as young as we can--is unappealing to me. Precociousness is a real thing, and I don't want to stand in the way of talent. To me, Castro for President is premature, but I have to admit the world belongs to the young now, who are going to have to find a way to live in it.

Tweet

Wednesday, March 13, 2019

Doing Justice by Preet Bharara

Audio CD, Expected pub: March 19th 2019 by Random House Audio Publishing Group, ISBN13: 9780525595762; Hardcover, Pub March 19th 2019 by Knopf Publishing Group, ISBN13: 9780525521129

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) tries cases that originate in New York’s financial centers, but also covers high-profile cases that have national and international resonance. Over two hundred lawyers and equally as many support staff work to administer law enforcement oversight to eight New York counties. Its resources, reach, and independence have earned it the nickname “The Sovereign Court” among members of the legal profession. SDNY attracts capable and driven prosecutors not distracted by limelight.

James Comey was once Chief Prosecutor of the SDNY for two years (2002-03) before he became Deputy Attorney General of the U.S. At the start of Donald Trump’s presidency, Preet Bharara was Chief Prosecutor of SDNY. He had taken on the role in 2009, nominated by then-President Obama, and developed a reputation as hard-charging.

Bharara was asked to resign his role by Jeff Sessions who had been appointed by the new President Donald Trump to head the Justice Department. Bharara refused. He was subsequently fired, leaving SDNY in March 2017, months into the Trump presidency. New York was Trump’s stomping ground, and the Southern District was the court most likely to prosecute crimes DJT committed, if any, before his ascension to the presidency.

Like anyone leading a group of intensely-committed, capable lawyers holding the powerful to account, Bharara had to develop a set of priorities and criterion which could direct his team to choose from among bad behaviors, determining the prosecutable. Every kind of crime has been tried in SDNY, from crimes of treason, terrorism, mob and gang violence to massive fraud and murder. Bharara reflects that “anybody can be guilty of anything.”

Divided into four sections, Bharara’s book examines first how successful prosecutors select their cases and prepare the evidence they will use in court. Certainly one consideration was whether a case was winnable or not but Comey, in his time as Chief Prosecutor for SDNY, argued that wasn’t the most important criterion: “If it’s a good case and the evidence supports it, you must bring it,” he said, even at the expense of possibly losing the case and adversely affecting one’s reputation and the reputation of the court.

Jesse Eisinger, now a reporter for ProPublica, reported extensively on high-profile cases in his book about the SDNY published in 2017 called The Chickenshit Club. He did not give the credit to Preet Bharara, who he saw as going after “easy” cases featuring insider trading rather than the rampant fraud and financial misconduct that nearly caused the world’s economy to melt down in 2007-08.

Bharara doesn’t address Eisinger’s criticisms directly but suggests getting the job done includes building cases that have the best possibility of success, and showing the public the judiciary is working on their behalf. It is hard to argue that Bharara wasn’t tough on crime. While he may not have secured convictions for the worst abuses of the biggest players responsible for the financial crisis, his offices had 85 straight convictions of insider-trading cases before losing one in 2014.

Bharara’s office also presided over a string of successes in prosecuting instances of cyber-crime, organized crime activity, art fraud, and instances of public corruption, among other things. Whether or not one thinks he was tough enough, his book is informative for what it tells us about our own justice system when it is performed in the biggest fishbowl in the land.

After first introducing the role of prosecutors and some of his cases, Bharara then moves to being effective in a court of law: looking at the importance of preparing the case as though you were arguing for the defendant, judging the judges, reading the court, and expecting unpredictable outcomes and verdicts. “Justice is not preordained.” How badly you want to win the case is often the most important ingredient in winning a case, pushing a prosecutor’s risk-aversion to the dangerous range.

Bharara reads the audio of the book himself, allowing him to tell the stories and place emphases where he wishes. The stories highlight what he was working for: providing a measure of justice to the powerless. Bharara’s job in the judiciary is a very important one in our three-legged system of government and he had a very long, uninterrupted run of it. His predecessors’ tenures could be measured in months. His observations are intrinsically interesting.

Bharara mentioned the importance of his family several times in the book, and knowing the all-encompassing nature of his job, one expects he missed many important family moments. He recounts a scene in which he proudly presents a laudatory article about himself and his work to his teenaged daughter to read. He waited impatiently while she carefully read and then slowly reread portions of the piece. Eventually she responded to his “Well?” with “You’re such a drama queen, Daddy.” Which may be the most succinct capture of a personality we are likely to enjoy.

Tweet

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) tries cases that originate in New York’s financial centers, but also covers high-profile cases that have national and international resonance. Over two hundred lawyers and equally as many support staff work to administer law enforcement oversight to eight New York counties. Its resources, reach, and independence have earned it the nickname “The Sovereign Court” among members of the legal profession. SDNY attracts capable and driven prosecutors not distracted by limelight.

James Comey was once Chief Prosecutor of the SDNY for two years (2002-03) before he became Deputy Attorney General of the U.S. At the start of Donald Trump’s presidency, Preet Bharara was Chief Prosecutor of SDNY. He had taken on the role in 2009, nominated by then-President Obama, and developed a reputation as hard-charging.