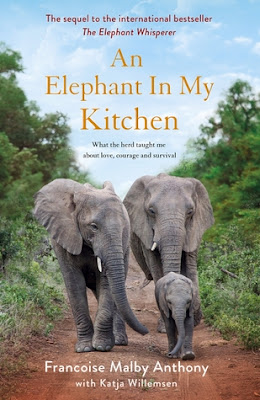

Hardcover, 336 pgs, Expected pub: Nov 5th 2019 by Thomas Dunne Books (first pub June 13th 2019), ISBN13: 9781250220141

For those who find animal emotions and inter-species friendships absorbing, this is a wonderful story about the ways rhinos, hippos, and elephants connect with each other and with humans.

Françoise Malay-Anthony was wife to the original Elephant Whisperer himself, Lawrence Anthony, who wrote a book of that name with famed nature-writer Graham Spence about his experiences creating an animal preserve in South Africa, called Thula Thula. At first Thula Thula was simply a preserve for herds of elephants whose habitat was disappearing. Soon it became apparent that poaching of elephant tusks and rhino horns was leaving vulnerable and traumatized babies to fend for themselves in dangerous territory.

Thula Thula gradually became known for emergency treatment of large animals prematurely separated from their mothers. A dedicated team of young volunteers from around the world worked hard to save endangered rhinos and baby elephants abandoned by their herd.

Leadership for this turn in the direction of Thula Thula, also a game reserve with hotel and bush drives for tourists to bring in money, came at the instigation of Françoise Malby-Anthony after the death of her husband, a time when she was anxious about managing the property without the extraordinary skills her husband possessed.

We learn of her vulnerability in light of world-class scam artists who sought to divert from her goal to make the environment better for animals in the wild. Her education in the ways of the wild—the wild world of tusk and horn poaching—is painful.

The viciousness of poaching by unscrupulous actors with enormous cash reserves has changed the entire focus of those in Africa seeking to preserve large animal habitat and populations. Trained security has had to devise ingenious methods of divining poachers plans and methods. This change in focus from trying to create a nurturing environment to defending territory and wildlife against indescribable violence is a disheartening change and a difficult way to live.

Compare those horrors with a young male elephant seeking the limelight—turning his rump to a jeep full of camera-toting watchers and twerking for the crowd. And an exploration of the character of rhino surprises readers utterly for what it tells us of their fearfulness and gentleness.

We likewise meet a hippo initially very suspicious of being asked to step into a green wading pool with a scant amount of water. We meet the handlers who become these distressed animals’ best buddies, teaching them to play despite their trauma, and protecting them as best they can from the nightmares that plague them.

If readers enjoy the stories in this book, one absolutely must make an attempt to locate a copy of The Elephant Whisperer referenced above because of what it adds in richness to the story and the description of the environment and told by a world-class raconteur.

Tweet

Sunday, November 3, 2019

Saturday, October 19, 2019

The Testaments by Margaret Atwood

Hardcover, 422 pgs, Pub Sept 10th 2019 by Nan A. Talese, ISBN13: 9780385543781, Series: The Handmaid's Tale #2 Lit Awards: Booker Prize (2019), Scotiabank Giller Prize Nominee (2019)

As this sequel to Atwood’s worldwide bestseller and Hulu serialized drama, The Handmaid’s Tale was coming to a close I grew anxious. ‘There are’t enough pages left to wrap this up,’ I thought, but I wasn’t giving Atwood and her editors enough credit.

The story is Atwood’s conversational response to readers who wanted to know what happened to characters left in extremis at the end of A Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood’s wonderful sense of humor brings the sharp-eyed, lumpy woman adorned in brown burlap and known as Aunt Lydia to life. Her diary is being composed as we read:

Two more points of view are given in short, discontinuous and not always parallel histories. A young girl growing up privileged in Gilead discovers at thirteen that she is considered marriageable. The horror of that notion stirs rebellion within her. An orphaned teen in Canada learns her guardians have been car bombed. She apparently has some debts to pay.

Atwood braids these three stories, giving each voice real distinction and character. Our mind’s eye has each firmly in sight as they gradually find themselves within arm’s reach of one another. One of the girls tells the other that Aunt Lydia is the “scariest of all the Aunts…You get the feeling she wants you to be better than you are…She looks at you as if she really sees you.” Hmm, yes.

What was most interesting to me as I blazed through this big book—it is very easy to read, a straight-line adventure story—is how Atwood could see so clearly certain social and political trends that are evidenced in our society now. Her clarity and comprehensiveness of view reveals so much about her own personality. She’d be a wonderful friend.

Vermont and Maine get top billing as states on Gilead’s border where residents are known to be willing to transport ‘grey market’ goods like lemons or escaping girls. A New Englander myself, I was disappointed New Hampshire was not similarly viewed until I considered the White Mountains would pose a significant barrier to anyone expecting to travel past them to the north.

In the end, I was gratified to discover Portsmouth, NH was chosen as a key location for by-sea person-smuggling from Gilead, just as it had been historically for black slaves of old seeking freedom in the north.

It is difficult to avoid Atwood’s premise that literature must be destroyed in a repressive state because new, creative notions about how to live are subversive. Atwood picked out for especial notice books that would be have an enormous impact on impressionable minds, like Jane Eyre, Anna Karenina, Tess of the D’Ubervilles, Paradise Lost, and Lives of Girls and Women.

I haven’t read the last but would like to, now. I might take issue with Paradise Lost. I read that again a couple years ago to compare it to Jamaica’s Kincaid’s memoir See Now Then and I can honestly say that book is too dense, particularly for young girls who are just learning to read. But Atwood probably knows better. When one’s library is limited, sometimes one’s understanding becomes sharpened.

When the girls in Gilead were finally able to read, it came as a shock to them that the Aunts had lied to them about the Bible. The Aunts had told the girls that the dismemberment story of the concubine, while horrific, was an act of sacrifice, a noble and charitable act. Reading the words themselves the girls discovered there was only degradation and hatred in the killing of an innocent.

Very very glad to hear from Margaret Atwood again. I miss her already.

View all my reviews Tweet

As this sequel to Atwood’s worldwide bestseller and Hulu serialized drama, The Handmaid’s Tale was coming to a close I grew anxious. ‘There are’t enough pages left to wrap this up,’ I thought, but I wasn’t giving Atwood and her editors enough credit.

The story is Atwood’s conversational response to readers who wanted to know what happened to characters left in extremis at the end of A Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood’s wonderful sense of humor brings the sharp-eyed, lumpy woman adorned in brown burlap and known as Aunt Lydia to life. Her diary is being composed as we read:

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, and I took the one most travelled by. It was littered with corpses, as such roads are. But as you will have noticed, my own corpse is not among them.”This turns out to be one page in Aunt Lydia’s apologia for misdeeds first forced upon her and then undertaken as a means to an end. Whose end we learn at the finish.

Two more points of view are given in short, discontinuous and not always parallel histories. A young girl growing up privileged in Gilead discovers at thirteen that she is considered marriageable. The horror of that notion stirs rebellion within her. An orphaned teen in Canada learns her guardians have been car bombed. She apparently has some debts to pay.

Atwood braids these three stories, giving each voice real distinction and character. Our mind’s eye has each firmly in sight as they gradually find themselves within arm’s reach of one another. One of the girls tells the other that Aunt Lydia is the “scariest of all the Aunts…You get the feeling she wants you to be better than you are…She looks at you as if she really sees you.” Hmm, yes.

What was most interesting to me as I blazed through this big book—it is very easy to read, a straight-line adventure story—is how Atwood could see so clearly certain social and political trends that are evidenced in our society now. Her clarity and comprehensiveness of view reveals so much about her own personality. She’d be a wonderful friend.

Vermont and Maine get top billing as states on Gilead’s border where residents are known to be willing to transport ‘grey market’ goods like lemons or escaping girls. A New Englander myself, I was disappointed New Hampshire was not similarly viewed until I considered the White Mountains would pose a significant barrier to anyone expecting to travel past them to the north.

In the end, I was gratified to discover Portsmouth, NH was chosen as a key location for by-sea person-smuggling from Gilead, just as it had been historically for black slaves of old seeking freedom in the north.

It is difficult to avoid Atwood’s premise that literature must be destroyed in a repressive state because new, creative notions about how to live are subversive. Atwood picked out for especial notice books that would be have an enormous impact on impressionable minds, like Jane Eyre, Anna Karenina, Tess of the D’Ubervilles, Paradise Lost, and Lives of Girls and Women.

I haven’t read the last but would like to, now. I might take issue with Paradise Lost. I read that again a couple years ago to compare it to Jamaica’s Kincaid’s memoir See Now Then and I can honestly say that book is too dense, particularly for young girls who are just learning to read. But Atwood probably knows better. When one’s library is limited, sometimes one’s understanding becomes sharpened.

When the girls in Gilead were finally able to read, it came as a shock to them that the Aunts had lied to them about the Bible. The Aunts had told the girls that the dismemberment story of the concubine, while horrific, was an act of sacrifice, a noble and charitable act. Reading the words themselves the girls discovered there was only degradation and hatred in the killing of an innocent.

“I feared I might lose my faith. If you’ve never had a faith, you will not understand what that means. You feel as if your best friend is dying, that everything that defined you is being burned away; that you’ll be left all alone.”We have to have some empathy, then, for those who will lose their faith, however weak it has become over the years, in a political party now called Republican. It is sad, this death of belief.

Very very glad to hear from Margaret Atwood again. I miss her already.

View all my reviews Tweet

Labels:

Canada,

fiction,

government,

literature,

Nan Talese,

Penguin,

PRH,

PRH Audio,

RH,

series

Monday, October 14, 2019

Coventry: Essays by Rachel Cusk

Hardcover, 256 pgs, Pub Sept 17th 2019 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux (first published August 20th 2019), ISBN13: 9780374126773

When I heard about a new book of essays by Rachel Cusk, I had two conflicting reactions: one was joy and one was sadness. Cusk is one of my favorite authors. She thinks deeply and can straightforwardly, analytically discuss her perceptions in involving prose but her characters can also demonstrate wildly ditzy intellectual fadeouts. I was sad to think I’d never have the quietness of mind in the current worldwide political upheaval to read her work in peace.

Then I saw a review by Clair Wills in the September 26 issue of The New York Review of Books. Cusk explained she also was experiencing a disconnection with something she is obviously attached to: writing. The review begins

Cusk doesn’t pander, doesn’t claim to be more than she is, and generally she stands firm on the ground she occupies but she does make tiny acknowledgements of fragility or uncertainty. Her opening essay, “Driving as a Metaphor,” starts out brassy with surety: “Where I live, there is always someone driving slowly on the road ahead.” We immediately get the impression this writer has much too many important things in her day without calculating in an extra five minutes for safety along a curvy coastline. Later in the same essay, she lets her attitude down a little and admits

She displays something of this heady teenagery cocktail of self-doubt and disdain in the title essay of her collection, “Coventry.” She describes boarding school and parents who could be aloof for reasons she never really understood. Their silence towards her she calls “being sent to Coventry.” Cusk may have felt she was sent to Coventry again as an adult by the reading public after her 2012 memoir, Aftermath, in which she gave voice to resentment over her divorce. But she was not wrong to concentrate on her own feelings in that memoir. How could she possibly know or consider her husband’s feelings in the midst of the personality destruction that is divorce?

In the NYRB review, Claire Mills writes that Cusk

This book of essays is divided into three parts, the first of which includes new work and the longish essay “Aftermath.” Part II is called A Tragic Pastime and includes a discussion of the sculptor Louise Bourgeois and a discussion on women’s writing called “Shakespeare’s Sisters,” among other things. Part III, entitled Classics & Bestsellers contains reprints of essays published earlier, including reviews of Edith Wharton & D.H. Lawrence, on Olivia Manning’s work, on Natalia Ginzburg, on Kazuo Ishiguro.

Cusk knows her writing has a lashing quality sometimes. She is comfortable with that. I am, too. Hey, life is not always a basket of cherries. She has been nothing but forthright that she will write what she thinks and feels, and you should take it or leave it. She would prefer you do not slam the door on the way out, thank you very much.

Below please find my reviews of Cusk's earlier work:

Saving Agnes, 1993

The Temporary, 1995 (not reviewed yet)

The Country Life, 1997

A Life's Work: On Becoming a Mother, 2002

The Lucky Ones, 2003

In the Fold, 2005

Arlington Park, 2006

The Bradshaw Variations, 2009

The Last Supper: A Summer in Italy, 2009

Aftermath: On Marriage & Separation, 2012

Outline, 2014

Medea, 2015

Transit, 2016

Kudos, 2018

Coventry: Essays, 2019

Tweet

When I heard about a new book of essays by Rachel Cusk, I had two conflicting reactions: one was joy and one was sadness. Cusk is one of my favorite authors. She thinks deeply and can straightforwardly, analytically discuss her perceptions in involving prose but her characters can also demonstrate wildly ditzy intellectual fadeouts. I was sad to think I’d never have the quietness of mind in the current worldwide political upheaval to read her work in peace.

Then I saw a review by Clair Wills in the September 26 issue of The New York Review of Books. Cusk explained she also was experiencing a disconnection with something she is obviously attached to: writing. The review begins

“Rachel Cusk is fascinated by silence. About five years ago she announced that she had given up on fiction. A prolific writer, she had by then published seven much-praised novels and three memoirs but, she explained, she was done with both genres…Fiction now seemed to her 'fake and embarrassing. Once you have suffered sufficiently, the idea of making up John and Jane and having them do things together seems utterly ridiculous.’”Ah. She caught me again. That’s exactly the way I feel about fiction when the world is burning.

Cusk doesn’t pander, doesn’t claim to be more than she is, and generally she stands firm on the ground she occupies but she does make tiny acknowledgements of fragility or uncertainty. Her opening essay, “Driving as a Metaphor,” starts out brassy with surety: “Where I live, there is always someone driving slowly on the road ahead.” We immediately get the impression this writer has much too many important things in her day without calculating in an extra five minutes for safety along a curvy coastline. Later in the same essay, she lets her attitude down a little and admits

“At busy or complicated junctions I find myself becoming self-conscious and nervous about reading the situation: I worry I don’t see things the way everyone else does, a quality that otherwise might be considered a strength. Sometimes, stuck on the coast road behind the slow drivers while they decide whether or not they want to turn left, it strikes me that the true danger of driving might lie in the capacity for subjectivity, and in the weapons it puts at subjectivity’s disposal.”Ah, once again. How can one not read Cusk when she writes like this, writing whatever she claims she cannot write. We need this particular mixture of vulnerability and steeliness to reassure us we are not mad about the apocalyptic shakiness of what we’d taken as firm ground.

She displays something of this heady teenagery cocktail of self-doubt and disdain in the title essay of her collection, “Coventry.” She describes boarding school and parents who could be aloof for reasons she never really understood. Their silence towards her she calls “being sent to Coventry.” Cusk may have felt she was sent to Coventry again as an adult by the reading public after her 2012 memoir, Aftermath, in which she gave voice to resentment over her divorce. But she was not wrong to concentrate on her own feelings in that memoir. How could she possibly know or consider her husband’s feelings in the midst of the personality destruction that is divorce?

In the NYRB review, Claire Mills writes that Cusk

“is not only willing to admit to her darkest instincts; she seems to revel in the anger they produce in others. How else to interpret the fact that—seven years after the ‘creative death’ that the response to Aftermath precipitated in her, she has republished the essay on which Aftermath was based in Coventry, her new collection of essays?”Mills’ interpretation of Cusk’s insistence on including this essay is not one I agree with. Were I to guess the reason, it would not be asserting Cusk persists in equating truth with honesty or truth as the opposite of stories. My guess would be that Cusk is asking us to think about truth and honesty, reality and fiction and see if there is much overlap. We are in the midst of a truth revolution, after all, and I feel quite sure she is just positing the question rather than supplying the answers.

This book of essays is divided into three parts, the first of which includes new work and the longish essay “Aftermath.” Part II is called A Tragic Pastime and includes a discussion of the sculptor Louise Bourgeois and a discussion on women’s writing called “Shakespeare’s Sisters,” among other things. Part III, entitled Classics & Bestsellers contains reprints of essays published earlier, including reviews of Edith Wharton & D.H. Lawrence, on Olivia Manning’s work, on Natalia Ginzburg, on Kazuo Ishiguro.

Cusk knows her writing has a lashing quality sometimes. She is comfortable with that. I am, too. Hey, life is not always a basket of cherries. She has been nothing but forthright that she will write what she thinks and feels, and you should take it or leave it. She would prefer you do not slam the door on the way out, thank you very much.

Below please find my reviews of Cusk's earlier work:

Saving Agnes, 1993

The Temporary, 1995 (not reviewed yet)

The Country Life, 1997

A Life's Work: On Becoming a Mother, 2002

The Lucky Ones, 2003

In the Fold, 2005

Arlington Park, 2006

The Bradshaw Variations, 2009

The Last Supper: A Summer in Italy, 2009

Aftermath: On Marriage & Separation, 2012

Outline, 2014

Medea, 2015

Transit, 2016

Kudos, 2018

Coventry: Essays, 2019

Tweet

Sunday, August 18, 2019

This Poison Will Remain by Fred Vargas, translated by Siân Reynolds

Paperback, 416 pgs, Pub: August 20th 2019 by Penguin Books (first published May 10th 2017)

Orig Title: Quand sort la recluse, ISBN13: 9780143133667, Series: Commissaire Adamsberg #11

Vargas doesn’t spare us the grisly details of outrageous crimes committed against defenseless girls and women, but never have I ever wanted to be in a mystery novel before. The characterizations of police officers and villagers are so full of personality, intelligence, and humor that one cannot help but wish these folks were by one’s side—or at least televised.

According to Wikipedia, four of the Vargas mystery series have been serialized for television. I saw one, once, years ago. It was painful, considering the renown of French cinema and the intrigue of the novels. it is definitely time for a new rendition.

Any new film series of the novels must be filmed in France and in French because the charm of the series is the utter French-ness of the interactions, the local dishes like the cabbage soup with onions and ham the officers eat nearly every night of the investigation, and endless bottles of Madiran.

Vargas has given us a convoluted mystery so dense with criminality that we scarcely know which way to turn. Just today I was listening to Vox's Today Explained podcast discussing the many thousands of rape kits in American cities which were never run for DNA: when the kits were finally examined, the entire body of knowledge around rape and serial rape has been turned on its head. It turns out that there were many, many more rapists than one ever thought possible, and one out of every five rapes is caused by a serial rapist.

There has been, as can be seen in the history revealed in this novel and in the untested rape kits languishing on shelves in police stations all over America, a dismissive attitude towards crimes against women. In this mystery, some truly horrifying crimes are described (thankfully in a matter-of-fact, non-inflammatory way) and some male attitudes are examined for bias. At one point Chief Inspector Adamsberg realizes describing his favorite female lieutenant as worth “ten men” would be better changed to “one woman.” Those of us who have worked with colleagues of both sexes are pleased Vargas made a point of chastising Adamsberg for old attitudes.

Vargas is known for the depth of her knowledge about medieval subjects and archeology and gradually she incorporates some of her encyclopedic knowledge in this more modern mystery. There is an archeological dig, and we learn how to find the site and what it takes to manage it. There is a medieval tie-in, but the shocking part is that it sounds medieval when in fact some of the events happened within recent history.

Chief Inspector Jean Baptiste Adamsberg always puts me in mind of Simenon’s Jules Maigret, though the two police chiefs are quite different in many ways. One difference is that Maigret, unless my memory is faulty, wasn't necessarily a masterful team leader. Adamsberg is far from alone. We are intimately familiar with his entire team and grow to rely on them to keep their chief operating in maximum intuition. Adamsberg's “tiny bubbles of gas in [his] brain” jiggle when he walks, stimulating thought. Not so far, then, from Poirot’s “little grey cells.”

This novel, originally published in May of 2017 by Flammarion of France, has been translated by Siân Reynolds, winner of many awards, including a coveted Dagger from Crime Writers’ Association. Reynolds is a professor emerita of French at the University of Stirling, Scotland. In her words,

More reviews of Vargas works:

The Chalk Circle Man

This Night's Foul Work

Tweet

Vargas doesn’t spare us the grisly details of outrageous crimes committed against defenseless girls and women, but never have I ever wanted to be in a mystery novel before. The characterizations of police officers and villagers are so full of personality, intelligence, and humor that one cannot help but wish these folks were by one’s side—or at least televised.

According to Wikipedia, four of the Vargas mystery series have been serialized for television. I saw one, once, years ago. It was painful, considering the renown of French cinema and the intrigue of the novels. it is definitely time for a new rendition.

Any new film series of the novels must be filmed in France and in French because the charm of the series is the utter French-ness of the interactions, the local dishes like the cabbage soup with onions and ham the officers eat nearly every night of the investigation, and endless bottles of Madiran.

Vargas has given us a convoluted mystery so dense with criminality that we scarcely know which way to turn. Just today I was listening to Vox's Today Explained podcast discussing the many thousands of rape kits in American cities which were never run for DNA: when the kits were finally examined, the entire body of knowledge around rape and serial rape has been turned on its head. It turns out that there were many, many more rapists than one ever thought possible, and one out of every five rapes is caused by a serial rapist.

There has been, as can be seen in the history revealed in this novel and in the untested rape kits languishing on shelves in police stations all over America, a dismissive attitude towards crimes against women. In this mystery, some truly horrifying crimes are described (thankfully in a matter-of-fact, non-inflammatory way) and some male attitudes are examined for bias. At one point Chief Inspector Adamsberg realizes describing his favorite female lieutenant as worth “ten men” would be better changed to “one woman.” Those of us who have worked with colleagues of both sexes are pleased Vargas made a point of chastising Adamsberg for old attitudes.

Vargas is known for the depth of her knowledge about medieval subjects and archeology and gradually she incorporates some of her encyclopedic knowledge in this more modern mystery. There is an archeological dig, and we learn how to find the site and what it takes to manage it. There is a medieval tie-in, but the shocking part is that it sounds medieval when in fact some of the events happened within recent history.

Chief Inspector Jean Baptiste Adamsberg always puts me in mind of Simenon’s Jules Maigret, though the two police chiefs are quite different in many ways. One difference is that Maigret, unless my memory is faulty, wasn't necessarily a masterful team leader. Adamsberg is far from alone. We are intimately familiar with his entire team and grow to rely on them to keep their chief operating in maximum intuition. Adamsberg's “tiny bubbles of gas in [his] brain” jiggle when he walks, stimulating thought. Not so far, then, from Poirot’s “little grey cells.”

This novel, originally published in May of 2017 by Flammarion of France, has been translated by Siân Reynolds, winner of many awards, including a coveted Dagger from Crime Writers’ Association. Reynolds is a professor emerita of French at the University of Stirling, Scotland. In her words,

”… Fred’s books are quirky and often fantastical, sometimes with historical elements, and much appreciated in France. They are about French characters usually in a recognizably French environment, and will necessarily seem a bit foreign to anglophone readers, so the aim is to make them enjoyable on their own terms – but in English.”This Reynolds does in spades. The novels are a remarkable glimpse of French culture and altogether are a marvelous series. Highly recommended.

More reviews of Vargas works:

The Chalk Circle Man

This Night's Foul Work

Tweet

Tuesday, August 6, 2019

The Helicopter Heist by Jonas Bonnier, translated by Alice Menzies

Paperback, 404 pgs, Pub May 28, 2019, Other Press Paperback Original. (first published April 2017), Original Title: Helikopterrånet translated by Alice Menzies, ISBN: 978-159051-950-9.

Have I got a summer read for you! This fictional Scandinavian thriller is based on true events, which makes it even more ravishing. I can’t wait for you to read it.

All you who love the TV series, movies, mysteries and thrillers to come out of Scandinavia, to say nothing of Karl Ove Knausgård’s bestselling fictional autobiography, are going to be reminded why you love those stories so much. This book has the daily life detail of Sweden that makes the journey so different from ordinary American novels.

To make it even more interesting, we are privy to the intimate thoughts and intentions of recent and not-so-recent migrants to Sweden, three of the main characters originally hailed from Lebanon, Iran, and Yugoslavia, though all are Swedish citizens now. Already we are interested. Add to that these folks struggled in their first years and turned to what appeared to be easier: theft and sometimes intricately designed robberies. Several of the characters met in jail.

Throw in some gorgeous Swedish blondes, female, at least one on the side of the law, the other working for the largest cash depot in Västberga, not too far from Stockholm, except there is water in between.

The beautiful blonde probably should have been harder to get, but one of the unattached, recently released, always-looking-for-an-angle young men is pointed towards her by a legendary thief, a thief who is in ‘retirement’ in a remote cottage filled with eight big labradors, and a stash of cash moldering in a root cellar.

The young man discovers the blonde is a talker, and she likes to talk about work, and that is the cash depot.

The absurdity of the plan to rob the depot is so far out that we can’t imagine these guys, who have already been to jail once and are so obviously outsiders in every way, can manage to pull it off without serious damage to their lives, if not their reputations. But still they persist. So many things go wrong: they lose key personnel regularly and must replace them with someone less knowledgeable or less skilled. The plan is wildly oversized in every way.

Then the police find out. They know what will happen, where and when. They prepare for weeks in advance. They contact the National Guard and SWAT. They have the judiciary involved and have bugged a key member of the team ten different ways.

The robbers are screwed.

That’s all I’m telling you, but believe me, this is about as stressful a situation as I can imagine. Each member of the team doesn’t know the other members well. It’s a total crapshoot. Wait until you see what happens. What struck me as most bizarre and yet so ridiculously true, is the media reaction. When the absurd robbery was underway, the entire world became riveted at this audacious plan.

This is a translated novel. There are some moments when one is completely aware one is not reading an ordinary American thriller of the more usual kind. This, my friends, is something completely different. If you did not get that Scandinavian vacation this year, never fear. You will be in Sweden for the two or three days it takes you to read this one.

And you will spend a lot less money.

This terrific novel has been optioned to be made into a Netflix film original starring and produced by Jake Gyllenhaal. Do not wait! Read the book first, if you have time in your book-reading schedule. I will make an admission: for almost a year now it has been very difficult for me to read fiction when our daily nonfictional lives are so eventful. Somehow this fiction of nonfiction is the perfect fit.

Enjoy!

Tweet

Have I got a summer read for you! This fictional Scandinavian thriller is based on true events, which makes it even more ravishing. I can’t wait for you to read it.

All you who love the TV series, movies, mysteries and thrillers to come out of Scandinavia, to say nothing of Karl Ove Knausgård’s bestselling fictional autobiography, are going to be reminded why you love those stories so much. This book has the daily life detail of Sweden that makes the journey so different from ordinary American novels.

To make it even more interesting, we are privy to the intimate thoughts and intentions of recent and not-so-recent migrants to Sweden, three of the main characters originally hailed from Lebanon, Iran, and Yugoslavia, though all are Swedish citizens now. Already we are interested. Add to that these folks struggled in their first years and turned to what appeared to be easier: theft and sometimes intricately designed robberies. Several of the characters met in jail.

Throw in some gorgeous Swedish blondes, female, at least one on the side of the law, the other working for the largest cash depot in Västberga, not too far from Stockholm, except there is water in between.

The beautiful blonde probably should have been harder to get, but one of the unattached, recently released, always-looking-for-an-angle young men is pointed towards her by a legendary thief, a thief who is in ‘retirement’ in a remote cottage filled with eight big labradors, and a stash of cash moldering in a root cellar.

The young man discovers the blonde is a talker, and she likes to talk about work, and that is the cash depot.

The absurdity of the plan to rob the depot is so far out that we can’t imagine these guys, who have already been to jail once and are so obviously outsiders in every way, can manage to pull it off without serious damage to their lives, if not their reputations. But still they persist. So many things go wrong: they lose key personnel regularly and must replace them with someone less knowledgeable or less skilled. The plan is wildly oversized in every way.

Then the police find out. They know what will happen, where and when. They prepare for weeks in advance. They contact the National Guard and SWAT. They have the judiciary involved and have bugged a key member of the team ten different ways.

The robbers are screwed.

That’s all I’m telling you, but believe me, this is about as stressful a situation as I can imagine. Each member of the team doesn’t know the other members well. It’s a total crapshoot. Wait until you see what happens. What struck me as most bizarre and yet so ridiculously true, is the media reaction. When the absurd robbery was underway, the entire world became riveted at this audacious plan.

This is a translated novel. There are some moments when one is completely aware one is not reading an ordinary American thriller of the more usual kind. This, my friends, is something completely different. If you did not get that Scandinavian vacation this year, never fear. You will be in Sweden for the two or three days it takes you to read this one.

And you will spend a lot less money.

This terrific novel has been optioned to be made into a Netflix film original starring and produced by Jake Gyllenhaal. Do not wait! Read the book first, if you have time in your book-reading schedule. I will make an admission: for almost a year now it has been very difficult for me to read fiction when our daily nonfictional lives are so eventful. Somehow this fiction of nonfiction is the perfect fit.

Enjoy!

Tweet

Labels:

crime,

fiction,

mystery,

Other Press,

Scandinavian,

true crime

Sunday, August 4, 2019

The Internet is My Religion by Jim Gilliam

Paperback, 194 pgs, Pub by NationBuilder (first published January 1st 2015), ISBN13: 9780996110402

You’re probably going to think a free memoir isn’t much—not interesting, not well-written, not worth bothering with. I picked it up at a conference not knowing it was a memoir. It sat around my house cluttering things until I decided to throw it out—but not until I glanced through it first.

Much later the same day it is all revolving in my head, leaving me feeling wonder, awe, thunderstruck surprise, joy, awe again. This is one helluva story, a creation story. a bildungsroman, an odyssey. And our hero—yes, emphatically, hero—emerges an adult, a moral adult caring about his fellow humans. His fellow humans care about him as well.

He is not bitter, or cynical, or any one of the things that lesser people may experience along the dark and scary road that can be our lives. His life surely trumps that of most of us, simply in terms of size: he is 6’9” and was down to 145 pounds at the height of his death-defying illness.

Since he tell us of his illness in the first pages, I am not giving away the story. No. That honor is still reserved for him because the bad things that happen are not really, ever, the story. It is what we did after that. And what Jim Gilliam did was to grab every bit of life he had left and use it.

By then he had discovered that God was not to be found in some cold pile of cathedral rocks somewhere or in the thundering denunciations of false prophets on TV. For him, God showed when we gathered together, in person or connected online, caring about and for one another, working towards a better, more perfect future. He calls that finding of connection a holy experience, and he is not wrong.

Gilliam is a technologist, and as such, one would expect his skills would not lie in writing. But this book, even if he had help, is beautifully done, full of moment, real insight, propulsion, and discovery. In a way, it is the tale of every man, though not every man has gotten there yet.

He will describe the moment he discovers falseness in the lessons taught him by his religious teachers, the moment the world begins to unravel around his family, the moment he discovers he must, no matter what, follow his own path to understanding.

What is so appealing about this journey is that Gilliam is guileless. He is not trying to teach us anything. He is explaining his journey, what he saw, and tells us what he thinks about what he saw. It is utterly fascinating because he has so much understanding of the events in his life.

Gilliam’s father and mother both were math majors and computer scientists of sorts in the computer field's early days. For business reasons his father lost an opportunity to develop one of the first software programs for personal computers at IBM and consequently turned to fundamentalist religion.

Gilliam grew up steeped in the language and an understanding of what computers could do, but was restricted from taking full advantage by the religiosity of his parents. He himself was very good at thinking like a scientist and took advanced classes while in high school so that he could enter college as a sophomore.

The hill separating him from his intellectual development became steeper just as he was finishing high school. I am not going to spoil the story arc. At no point did this 180-page small format paperback ever become weighted down with intent or causation. We just have the clean progression of one boy into man into—that word again—hero.

His understanding that there is something godly in human connection, in striving together for good, is exactly what people discover in moments of human happiness and fulfillment. While he rejected the morality in which he was raised, as I did, I wonder if somehow it wasn’t good preparation for recognizing morality when he saw it, finally.

Personally, I can’t think of a more absorbing, unputdownable story. Get it if you can. It is a wonderful, thought-provoking personal history.

Tweet

You’re probably going to think a free memoir isn’t much—not interesting, not well-written, not worth bothering with. I picked it up at a conference not knowing it was a memoir. It sat around my house cluttering things until I decided to throw it out—but not until I glanced through it first.

Much later the same day it is all revolving in my head, leaving me feeling wonder, awe, thunderstruck surprise, joy, awe again. This is one helluva story, a creation story. a bildungsroman, an odyssey. And our hero—yes, emphatically, hero—emerges an adult, a moral adult caring about his fellow humans. His fellow humans care about him as well.

He is not bitter, or cynical, or any one of the things that lesser people may experience along the dark and scary road that can be our lives. His life surely trumps that of most of us, simply in terms of size: he is 6’9” and was down to 145 pounds at the height of his death-defying illness.

Since he tell us of his illness in the first pages, I am not giving away the story. No. That honor is still reserved for him because the bad things that happen are not really, ever, the story. It is what we did after that. And what Jim Gilliam did was to grab every bit of life he had left and use it.

By then he had discovered that God was not to be found in some cold pile of cathedral rocks somewhere or in the thundering denunciations of false prophets on TV. For him, God showed when we gathered together, in person or connected online, caring about and for one another, working towards a better, more perfect future. He calls that finding of connection a holy experience, and he is not wrong.

Gilliam is a technologist, and as such, one would expect his skills would not lie in writing. But this book, even if he had help, is beautifully done, full of moment, real insight, propulsion, and discovery. In a way, it is the tale of every man, though not every man has gotten there yet.

He will describe the moment he discovers falseness in the lessons taught him by his religious teachers, the moment the world begins to unravel around his family, the moment he discovers he must, no matter what, follow his own path to understanding.

What is so appealing about this journey is that Gilliam is guileless. He is not trying to teach us anything. He is explaining his journey, what he saw, and tells us what he thinks about what he saw. It is utterly fascinating because he has so much understanding of the events in his life.

Gilliam’s father and mother both were math majors and computer scientists of sorts in the computer field's early days. For business reasons his father lost an opportunity to develop one of the first software programs for personal computers at IBM and consequently turned to fundamentalist religion.

Gilliam grew up steeped in the language and an understanding of what computers could do, but was restricted from taking full advantage by the religiosity of his parents. He himself was very good at thinking like a scientist and took advanced classes while in high school so that he could enter college as a sophomore.

The hill separating him from his intellectual development became steeper just as he was finishing high school. I am not going to spoil the story arc. At no point did this 180-page small format paperback ever become weighted down with intent or causation. We just have the clean progression of one boy into man into—that word again—hero.

His understanding that there is something godly in human connection, in striving together for good, is exactly what people discover in moments of human happiness and fulfillment. While he rejected the morality in which he was raised, as I did, I wonder if somehow it wasn’t good preparation for recognizing morality when he saw it, finally.

Personally, I can’t think of a more absorbing, unputdownable story. Get it if you can. It is a wonderful, thought-provoking personal history.

Tweet

Wednesday, July 31, 2019

Gerrymandering in America by Anthony J. McGann, Charles Anthony Smith, Michael Latner, Alex Keena

Paperback, 272 pgs, Pub July 11th 2017 by Cambridge University Press, ISBN13: 9781316507674

This academic look at gerrymandering—how to measure it, how one does it most effectively, and what exactly are its effects—was published in 2016 by Cambridge University Press—yes, the British one. One author, Anthony McGann, is from Glasgow. The other three authors, Charles A Smith, Michael Latner, and Alex Keena, are all professors from CA institutions.

For someone new to the term gerrymandering, this definitely won’t be the easiest entry, but to someone more familiar, it has enlightening bits. They talk quite a lot about Pennsylvania, one of the worst gerrymandered states in the country. You may have heard the State Supreme Court in PA deemed the congressional maps so egregiously gerrymandered they ended up providing a new map to a recalcitrant state legislature in 2018.

After 2011 redistricting, though Democrats had won over 50% of the votes for congresspeople in the state, they managed to win only 5 of 18 congressional seats. After the State Supreme Court passed down the new maps in 2018, Democrats won 9 of 18 seats.

Actually, depending on where Democrats reside, there is no reason why 50% of votes should necessarily translate into half the seats. No one really cared if they didn’t. It was the relative skew that was offensive, and the ugly fact that the state legislators in office did nothing with their supermajority but pass innocuous resolutions, e.g., Dec 12 is Polar Bear Day, and Sept 13 is Healthy Heart Day, and avoid talking about the 18 cities in PA, including Pittsburgh, with lead levels higher than Flint, Michigan.

In Pennsylvania (and Wisconsin and Michigan and…) today, voters must face the horrible problem of having their state legislative districts so gerrymandered that no one will even run against incumbents. We can’t even vote the crooks out.

After the June 2019 SCOTUS decision not to deal with any more gerrymandering problems in federal courts, disenfranchised voters will be forced to bring maps redistricted after the 2020 Census through the state courts again. Meanwhile, nonpartisan volunteer organizations are blanketing the state with petitions to urge legislators to “do the right thing” and voluntarily give up their constitutional right to draw district lines, for the sake of fairness and democracy. So far, legislators haven’t shown interest in anybody's constitutional rights beyond their own.

Claims have been made by some that the self-sorting voters do along partisan lines into cities and rural areas is responsible for the bias in results, not the intentional gerrymander. However, these scholars have concluded self-sorting is not responsible for the extent of the bias in results, and gives examples of several states also with city/rural dichotomies that do not exhibit partisan bias. Many states exhibit extreme partisan bias, Pennsylvania among them.

There is a trade-off between seat maximization and incumbent protection. Regions with competitors packed into one district have extraordinary non-responsive voting blocks in the surrounding districts.

Worst of all, in reviewing what I wanted to say about the pitiable position Pennsylvania’s manipulative legislators have left us in, near the top of the Top Ten Exhibiting Partisan Bias… worst yet is that the states above Pennsylvania in #4 place are states we never hear anything about. No, they are NOT Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin North Carolina, or Maryland. They are Alabama, Mississippi, Missouri, states with large populations of African American voters so used to being beat up and beat down they don’t even protest anymore. Of course the government is going to steal their vote. Oh, it is enraging.

A summary of the difference between Boundary Commissions and U.S. election districts and commissions: 1) Britain is not two party, which makes a huge difference in the attempt to gerrymander. People have been known to calculate their vote in order to stymie any gerrymander. That is, there is tactical voting. 2) A source of bias is not a gerrymander but is caused by differential turnout. “Labour tends to win when fewer people vote.” 3) Districts are not the same size nor same population as is required in U.S. congressional and legislative districts. This presents a small bias towards Labour. 4) The authors are not sure what the last advantage is: “If there is something about geographical distribution of support that has given Labour an advantage, it is not clear what it is.” One explanation…is that Labour appears disproportionately successful at winning close races.

Anyway, they conclude there was a partisan bias in Britain for whatever reason after 2010, but it seems to have disappeared by 2015. The Boundary Commissions have no real effect at preventing partisan bias because it explicitly cannot take partisan bias into account: “Fairness between the political parties is not a factor that can be considered.”

Tweet

This academic look at gerrymandering—how to measure it, how one does it most effectively, and what exactly are its effects—was published in 2016 by Cambridge University Press—yes, the British one. One author, Anthony McGann, is from Glasgow. The other three authors, Charles A Smith, Michael Latner, and Alex Keena, are all professors from CA institutions.

For someone new to the term gerrymandering, this definitely won’t be the easiest entry, but to someone more familiar, it has enlightening bits. They talk quite a lot about Pennsylvania, one of the worst gerrymandered states in the country. You may have heard the State Supreme Court in PA deemed the congressional maps so egregiously gerrymandered they ended up providing a new map to a recalcitrant state legislature in 2018.

After 2011 redistricting, though Democrats had won over 50% of the votes for congresspeople in the state, they managed to win only 5 of 18 congressional seats. After the State Supreme Court passed down the new maps in 2018, Democrats won 9 of 18 seats.

Actually, depending on where Democrats reside, there is no reason why 50% of votes should necessarily translate into half the seats. No one really cared if they didn’t. It was the relative skew that was offensive, and the ugly fact that the state legislators in office did nothing with their supermajority but pass innocuous resolutions, e.g., Dec 12 is Polar Bear Day, and Sept 13 is Healthy Heart Day, and avoid talking about the 18 cities in PA, including Pittsburgh, with lead levels higher than Flint, Michigan.

In Pennsylvania (and Wisconsin and Michigan and…) today, voters must face the horrible problem of having their state legislative districts so gerrymandered that no one will even run against incumbents. We can’t even vote the crooks out.

After the June 2019 SCOTUS decision not to deal with any more gerrymandering problems in federal courts, disenfranchised voters will be forced to bring maps redistricted after the 2020 Census through the state courts again. Meanwhile, nonpartisan volunteer organizations are blanketing the state with petitions to urge legislators to “do the right thing” and voluntarily give up their constitutional right to draw district lines, for the sake of fairness and democracy. So far, legislators haven’t shown interest in anybody's constitutional rights beyond their own.

Claims have been made by some that the self-sorting voters do along partisan lines into cities and rural areas is responsible for the bias in results, not the intentional gerrymander. However, these scholars have concluded self-sorting is not responsible for the extent of the bias in results, and gives examples of several states also with city/rural dichotomies that do not exhibit partisan bias. Many states exhibit extreme partisan bias, Pennsylvania among them.

There is a trade-off between seat maximization and incumbent protection. Regions with competitors packed into one district have extraordinary non-responsive voting blocks in the surrounding districts.

"Put bluntly, if you can pack your opponents into a single district where they win 80% of the vote, you can create [surrounding] districts where you have a 7.5% advantage. It is notable that the number of “incumbent protection” districting plans declined sharply between 2002 and 2012. It seems that more states are districting for national partisan advantage, even though it makes their incumbents slightly more vulnerable.”The authors make a distinction between partisan bias and responsiveness. “If there is partisan bias, then one party is advantaged over the other…If a districting system has high responsiveness, then it gives an advantage to the larger party, whichever party that happens to be.”

Worst of all, in reviewing what I wanted to say about the pitiable position Pennsylvania’s manipulative legislators have left us in, near the top of the Top Ten Exhibiting Partisan Bias… worst yet is that the states above Pennsylvania in #4 place are states we never hear anything about. No, they are NOT Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin North Carolina, or Maryland. They are Alabama, Mississippi, Missouri, states with large populations of African American voters so used to being beat up and beat down they don’t even protest anymore. Of course the government is going to steal their vote. Oh, it is enraging.

“...districting is mathematically a very, very difficult problem...”The California independent redistricting commission may have been partly modeled on the British iteration, called Boundary Commissions. Boundary Commissions are explicitly forbidden from considering partisan data when deciding their maps. This has actually led, in CA as well, to skews that were unintentional but partisan in fact. As a result, CA commissions have made the unusual request that they must consider partisan data in order to avoid it.

A summary of the difference between Boundary Commissions and U.S. election districts and commissions: 1) Britain is not two party, which makes a huge difference in the attempt to gerrymander. People have been known to calculate their vote in order to stymie any gerrymander. That is, there is tactical voting. 2) A source of bias is not a gerrymander but is caused by differential turnout. “Labour tends to win when fewer people vote.” 3) Districts are not the same size nor same population as is required in U.S. congressional and legislative districts. This presents a small bias towards Labour. 4) The authors are not sure what the last advantage is: “If there is something about geographical distribution of support that has given Labour an advantage, it is not clear what it is.” One explanation…is that Labour appears disproportionately successful at winning close races.

Anyway, they conclude there was a partisan bias in Britain for whatever reason after 2010, but it seems to have disappeared by 2015. The Boundary Commissions have no real effect at preventing partisan bias because it explicitly cannot take partisan bias into account: “Fairness between the political parties is not a factor that can be considered.”

Tweet

Thursday, July 25, 2019

Gerrymandering by Franklin L. Kury

Paperback, 132 pgs, Pub May 4th 2018 by Hamilton, ISBN13: 9780761870258

Franklin Kury is a former member of the Pennsylvania State Senate, serving 1973-1980. Just last year he published a book about Pennsylvania’s bout of gerrymandering after the 2010 census, documented as one of the worst in the nation.

The League of Women Voters challenge to the maps yielded a win for voters. In 2018 the state Supreme Court handed down what has turned out to be a landmark ruling:

Gerrymandered states wonder what exactly that means. If the judiciary at the federal level can’t make the call on what is a gerrymander, why can the state courts decide these things? This is the source of the disagreement between the assent and dissent on the latest SCOTUS decision concerning gerrymandering.

Kury’s book came out before the latest SCOTUS decision, so is merely speculative on how the court would weigh in. Meanwhile, he describes the problem Pennsylvania continues to have with gerrymanders in the electoral districts for state legislative offices. According to the PA constitution, “municipalities and counties should not be divided more than is required by population plus one.”

By that criterion, Pennsylvania’s Butler County should have three state house members, but has seven. It also has three senators, when it should have only one based upon population. Montgomery County should have 13 state house members but it has 18 and twice as many senators -- 6 v. 3. The list goes on. And that doesn’t even touch the problem of cities, chopped to bits, pieces of which are roped in with their rural surrounds.

Pennsylvania’s legislative electoral maps effectively shut out all but one party in power. That party, the Republicans, have such a firm hold on their caucus they don’t even primary their candidates. They hold private local meetings wherein they choose who will go on the ballot. There is only one candidate per office when it comes time to primary. And of course the general has that same single candidate once again.

The minority challenger party can have a raft of candidates to choose from, but because they are not using ranked-choice voting, sometimes a less desirable candidate comes up higher on the list than anyone wants. And since Republican ballots are single candidates, Dems with more than one candidate per office will suffer the count. Don’t even mention Independents or third-party voters: they can’t vote in primaries unless they register with one of the major parties.

Kury’s book explains where the term ‘gerrymandering’ comes from and moves quickly to discussing RedMAP and the Republican attempt to take back the House of Representatives, which they calculated might be done by focusing on ‘cheaper’ state races and controlling redistricting. By ‘cheaper’ they meant less expensive purchases of advertisements, events, and media influencers than trying to put in national candidates the same way. They were right about that.

What is riveting about gerrymandering is that it is so clearly unfair. Pennsylvania is a state that used to take its fairness and integrity seriously. Once awakened to partisan gerrymandering, it is difficult not to see it everywhere. Even states who have tried to fix the problem by instituting an independent citizens redistricting commission have been accused of gerrymandering because of their mapping choices. Kury writes up a few of the more famous instances of independent commissions, which it turns out, come in many different sizes and with a wide range of decision-making authority.

Best of all, Kury’s book lists resources that will help any individual struggling with redistricting issues in their own state to find what happened elsewhere. He discusses redistricting software and some of the issues that arise when one tries to map districts from scratch. That’s the thing with gerrymandering: one wants to see how others dealt with it to see if their solutions will work. For Pennsylvania, the struggle to claw back voters rights continues.

Tweet

Franklin Kury is a former member of the Pennsylvania State Senate, serving 1973-1980. Just last year he published a book about Pennsylvania’s bout of gerrymandering after the 2010 census, documented as one of the worst in the nation.

The League of Women Voters challenge to the maps yielded a win for voters. In 2018 the state Supreme Court handed down what has turned out to be a landmark ruling:

“For the first time, those seeking a new Congressional districting plan went to the state courts and relied solely on state law.”SCOTUS relied on this ruling as they looked at gerrymandering in their decision handed down at the end of June 2019. SCOTUS decided it would not decide gerrymander cases through the judiciary at the federal level because it is inherently political. They cited the PA decision to show that state courts can decide these things, effectively handing the fight back to the states.

Gerrymandered states wonder what exactly that means. If the judiciary at the federal level can’t make the call on what is a gerrymander, why can the state courts decide these things? This is the source of the disagreement between the assent and dissent on the latest SCOTUS decision concerning gerrymandering.

Kury’s book came out before the latest SCOTUS decision, so is merely speculative on how the court would weigh in. Meanwhile, he describes the problem Pennsylvania continues to have with gerrymanders in the electoral districts for state legislative offices. According to the PA constitution, “municipalities and counties should not be divided more than is required by population plus one.”

By that criterion, Pennsylvania’s Butler County should have three state house members, but has seven. It also has three senators, when it should have only one based upon population. Montgomery County should have 13 state house members but it has 18 and twice as many senators -- 6 v. 3. The list goes on. And that doesn’t even touch the problem of cities, chopped to bits, pieces of which are roped in with their rural surrounds.

Pennsylvania’s legislative electoral maps effectively shut out all but one party in power. That party, the Republicans, have such a firm hold on their caucus they don’t even primary their candidates. They hold private local meetings wherein they choose who will go on the ballot. There is only one candidate per office when it comes time to primary. And of course the general has that same single candidate once again.

The minority challenger party can have a raft of candidates to choose from, but because they are not using ranked-choice voting, sometimes a less desirable candidate comes up higher on the list than anyone wants. And since Republican ballots are single candidates, Dems with more than one candidate per office will suffer the count. Don’t even mention Independents or third-party voters: they can’t vote in primaries unless they register with one of the major parties.

Kury’s book explains where the term ‘gerrymandering’ comes from and moves quickly to discussing RedMAP and the Republican attempt to take back the House of Representatives, which they calculated might be done by focusing on ‘cheaper’ state races and controlling redistricting. By ‘cheaper’ they meant less expensive purchases of advertisements, events, and media influencers than trying to put in national candidates the same way. They were right about that.

What is riveting about gerrymandering is that it is so clearly unfair. Pennsylvania is a state that used to take its fairness and integrity seriously. Once awakened to partisan gerrymandering, it is difficult not to see it everywhere. Even states who have tried to fix the problem by instituting an independent citizens redistricting commission have been accused of gerrymandering because of their mapping choices. Kury writes up a few of the more famous instances of independent commissions, which it turns out, come in many different sizes and with a wide range of decision-making authority.

Best of all, Kury’s book lists resources that will help any individual struggling with redistricting issues in their own state to find what happened elsewhere. He discusses redistricting software and some of the issues that arise when one tries to map districts from scratch. That’s the thing with gerrymandering: one wants to see how others dealt with it to see if their solutions will work. For Pennsylvania, the struggle to claw back voters rights continues.

Tweet

Sunday, July 7, 2019

Beating Guns: Hope for People Who Are Weary of Violence by Shane Clairborne & Michael Martin

Paperback, 288 pgs, Pub March 5th 2019 by Brazos Press, ISBN13: 9781587434136

Shane Clairborne, Christian activist and motivational speaker, and Michael Martin, former Mennonite pastor and founder of RAWtools.com, a company that turns donated weapons into gardening tools, wrote this book about the work they do together. Tired of gun violence in America, the two are traveling the country and speaking out to remind us we are not where we want to be as a country.

Research shows that most Americans already agree with them. Why are our children still dying in mass shootings? We are being help hostage by a profit-making industry that cares little about the lives lost to inadequate gun controls; our “religious right” is actually wrong and has only been mouthing Christianity and not living it; there is a skewed religiosity and a profit motive among preachers and teachers as well, like Jerry Falwell Jr at Liberty University. The words of these two authors reassure me that my reason has not been deceived: I have long thought there is a rot somewhere in traditional religions that is killing the source of our morality.

This long conversational history rounds the bases on reasons we should consider turning our guns into garden tools and shares the sources of the authors’ own decision to spend their energies on this effort. They teach, better than any pastor I’ve heard in many years. They quote the Bible, Jesus, and leaders of nonviolence movements in the past, pointing to the undeniable bottom line that Christians are not meant to arm themselves against those who come to hurt them. They are meant to do as Jesus did during his years on earth: defuse the situation, change the subject, turn the other cheek, and yes, die for one’s beliefs. Because the idea for which he died will never die.

Every few pages, like tombstone markers, pages describe one or another incident of gun violence, naming the victims and reminding us of the circumstances. Most of these twenty or so tombstones are as familiar to us as our own names, horrific and shocking incidences of unnecessary and impersonal violence by people mad with delusion. It is hard to understand how our politicians dare stand in front of us; dare to speak a word to us without offering to protect us by controlling guns.

Shane and Mike have done their research on the NRA, and do not hesitate to point to the ways our nation’s dialogue has been warped by the nominally nonprofit’s profit motive. The NRA boasts some five million members. If we do the math—one-third of 325 million U.S. residents are gun owners—over 90 percent of gun owners are not represented by the NRA. But their lobbying arm keeps politicians flush with cash for their campaigns. This trade-off should be outlawed, but even our courts have refused to look after the people’s interests with regard to this matter.

A chapter detailing “the absurd” of pride in gun ownership recount instances of folly: an instance where a groom posing with a rifle at his wedding accidentally shoots his photographer. Or the Hello Kitty assault rifle handled by a seven-year-old that managed to kill a three-year-old.

In a chapter named “Mythbusting” the authors address things we might be persuaded to believe without evidence, like “Stranger Danger.” Actually, we’re far more likely to be killed by people we know well. Regarding the old standby, “Guns Keep Us Safe,” the argument is so shopworn by now that statistics start to sound like “the absurd” chapter. The men discuss race and guns, veterans and guns, women and guns, and they quote Justice John Paul Stevens of the U.S. Supreme Court as saying the Second Amendment is “a relic of the 18th century.”

This is a worthwhile book, giving us the language and statistics we will need to surprise our opponents into silence, unable to find a reasonable comeback if we are using logic and not emotion. The U.S. has about 270 million guns in circulation, 42% of guns in the world, or 90 for every 100 people. Forty-four percent of Americans personally know someone who has been shot, accidentally or intentionally. Christians are challenged to explain the fact that 41% of white evangelicals own a gun, compared to 30% of the general population. The authors ridicule the defenses they’ve heard for gun ownership among religious people and point out that Jesus teaches countering aggression with creativity, not submission:

Shane Clairborne is a Philadelphian when he’s at home, and is founder of The Simple Way, a social services organization in Philly. He is President of Red Letter Christians, a Christian group which mobilizes individuals into a movement of believers who live out Jesus’ counter-cultural teachings and tries to combine Jesus and justice.

Michael Martin teaches nonviolent confrontational skills in addition to beating weapons into ploughshares. These are the kind of Christians I like and admire and would travel to hear.

Tweet

Shane Clairborne, Christian activist and motivational speaker, and Michael Martin, former Mennonite pastor and founder of RAWtools.com, a company that turns donated weapons into gardening tools, wrote this book about the work they do together. Tired of gun violence in America, the two are traveling the country and speaking out to remind us we are not where we want to be as a country.

Research shows that most Americans already agree with them. Why are our children still dying in mass shootings? We are being help hostage by a profit-making industry that cares little about the lives lost to inadequate gun controls; our “religious right” is actually wrong and has only been mouthing Christianity and not living it; there is a skewed religiosity and a profit motive among preachers and teachers as well, like Jerry Falwell Jr at Liberty University. The words of these two authors reassure me that my reason has not been deceived: I have long thought there is a rot somewhere in traditional religions that is killing the source of our morality.

This long conversational history rounds the bases on reasons we should consider turning our guns into garden tools and shares the sources of the authors’ own decision to spend their energies on this effort. They teach, better than any pastor I’ve heard in many years. They quote the Bible, Jesus, and leaders of nonviolence movements in the past, pointing to the undeniable bottom line that Christians are not meant to arm themselves against those who come to hurt them. They are meant to do as Jesus did during his years on earth: defuse the situation, change the subject, turn the other cheek, and yes, die for one’s beliefs. Because the idea for which he died will never die.

Every few pages, like tombstone markers, pages describe one or another incident of gun violence, naming the victims and reminding us of the circumstances. Most of these twenty or so tombstones are as familiar to us as our own names, horrific and shocking incidences of unnecessary and impersonal violence by people mad with delusion. It is hard to understand how our politicians dare stand in front of us; dare to speak a word to us without offering to protect us by controlling guns.

Shane and Mike have done their research on the NRA, and do not hesitate to point to the ways our nation’s dialogue has been warped by the nominally nonprofit’s profit motive. The NRA boasts some five million members. If we do the math—one-third of 325 million U.S. residents are gun owners—over 90 percent of gun owners are not represented by the NRA. But their lobbying arm keeps politicians flush with cash for their campaigns. This trade-off should be outlawed, but even our courts have refused to look after the people’s interests with regard to this matter.

A chapter detailing “the absurd” of pride in gun ownership recount instances of folly: an instance where a groom posing with a rifle at his wedding accidentally shoots his photographer. Or the Hello Kitty assault rifle handled by a seven-year-old that managed to kill a three-year-old.

In a chapter named “Mythbusting” the authors address things we might be persuaded to believe without evidence, like “Stranger Danger.” Actually, we’re far more likely to be killed by people we know well. Regarding the old standby, “Guns Keep Us Safe,” the argument is so shopworn by now that statistics start to sound like “the absurd” chapter. The men discuss race and guns, veterans and guns, women and guns, and they quote Justice John Paul Stevens of the U.S. Supreme Court as saying the Second Amendment is “a relic of the 18th century.”

This is a worthwhile book, giving us the language and statistics we will need to surprise our opponents into silence, unable to find a reasonable comeback if we are using logic and not emotion. The U.S. has about 270 million guns in circulation, 42% of guns in the world, or 90 for every 100 people. Forty-four percent of Americans personally know someone who has been shot, accidentally or intentionally. Christians are challenged to explain the fact that 41% of white evangelicals own a gun, compared to 30% of the general population. The authors ridicule the defenses they’ve heard for gun ownership among religious people and point out that Jesus teaches countering aggression with creativity, not submission:

”evil can be opposed without being mirrored…oppressors can be resisted without being emulated…enemies can be neutralized without being destroyed.”Finally the authors remind us that the opposite of love is not hate, but fear. They explain that “fear not” is the most reiterated commandment n the Bible and that powerful people who are afraid are the most dangerous elements in the world. We really do have more to fear from fear itself. We need courage to stand in front of armed neighbors and say no to guns, but these men are handing us the tools.

Shane Clairborne is a Philadelphian when he’s at home, and is founder of The Simple Way, a social services organization in Philly. He is President of Red Letter Christians, a Christian group which mobilizes individuals into a movement of believers who live out Jesus’ counter-cultural teachings and tries to combine Jesus and justice.

Michael Martin teaches nonviolent confrontational skills in addition to beating weapons into ploughshares. These are the kind of Christians I like and admire and would travel to hear.

Tweet

Labels:

America,

Brazos,

nonfiction,

politics,

psychology,

religion

Saturday, July 6, 2019

The Moment of Lift by Melinda Gates

Hardcover, 273 pgs, Pub April 23rd 2019 by Flatiron Books, ISBN13: 9781250313577

Melinda Gates has a famous name and job, but who knows what she actually does? Running a foundation with assets exceeding that of many countries must carry enormous stresses, particularly for people who understand that injecting cash into a problem may actually make the problem grow. What courage it must take just to try.

This had to have been a hard book to write, what with a crushing schedule, children, and weighty responsibilities, to say nothing of the disparate and discrete problems of women on different continents. I am not saying there aren’t similarities among women’s experiences the world over; I’m saying that, perhaps for the purposes of this book, on each continent Gates honed in on a different critical problem among women that she might be able to affect. In Africa, she showed us women responsible for field work and cultivation. In South Asia, we look at sex workers. In America, it was education. In every country the message was about empowerment and equality.

Gates sounds tentative and naïve to begin which may help her audience connect with her experience. But she has some insights sprinkled all the way along as we follow her progress from Catholic-school Texan to one of the few female programmers at a gung-ho win-at-any-cost Microsoft. Two early insights:

When speaking of her Catholicism and her support for birth control, that is, the notion that women must be able to control their own births, Gates says that religion and birth control should not be incompatible. She feels on strong moral ground and welcomes guidance from priests, nuns, and laypeople but “ultimately moral questions are personal questions. Majorities don’t matter on issues of conscience.” Drop mike. My hero. She gives me language to speak to critics who wish to roll back women’s right to choose. It’s not an easy decision but it is a woman’s decision. Otherwise, Christian critics, why did God give this ability to women alone?

Melinda shares some empowerment struggles of her own—in a company and in a household with Bill Gates. She was intimidated, but can you blame her? With support from Bill and from colleagues and friends, she managed to develop her innate ability to cooperate and thereby manage high-performing teams, both at the company and later at the foundation.

Later, Gates asks how does disrespect for women grow within a child suckling at his mother’s breast? Gates places the blame squarely on religion: “Disrespect for women grows when religions are dominated by men.” That is a brave stance, the articulation of which I am grateful. I also came to that conclusion, and it felt a lonely one. I wondered how my moral grounding felt so strong when I learned what I had in the Catholic tradition also. Perhaps our reactions are something along the lines of the questioning, probing Jesuitical tradition?

Women! stand up and show them how to both nurture and progress. Democrats and Republicans, we have way more in common as women than we have differences as political animals. And we have as much at stake. Those who are already empowered can make decisions on their own, so aren’t intimidated by women who may occasionally disagree. Isn't this how we learn? Those who seek empowerment can find it with other women, so join us. I definitely think there is room to work together to achieve something we haven’t yet managed here in the U.S. and need badly: coherence.

Gates’ last point is one close to the hearts of every mother, teacher, groundbreaker:

Gates has written a thought-provoking and generous book, sharing much of what she has been given.

Tweet

Melinda Gates has a famous name and job, but who knows what she actually does? Running a foundation with assets exceeding that of many countries must carry enormous stresses, particularly for people who understand that injecting cash into a problem may actually make the problem grow. What courage it must take just to try.

This had to have been a hard book to write, what with a crushing schedule, children, and weighty responsibilities, to say nothing of the disparate and discrete problems of women on different continents. I am not saying there aren’t similarities among women’s experiences the world over; I’m saying that, perhaps for the purposes of this book, on each continent Gates honed in on a different critical problem among women that she might be able to affect. In Africa, she showed us women responsible for field work and cultivation. In South Asia, we look at sex workers. In America, it was education. In every country the message was about empowerment and equality.